From Apron Factory to Paris Runways

Few fashion houses that have made their way to Paris runways have started as humbly as Akris. It’s the extraordinary story of a farmer’s daughter who started with one sewing machine and the wish to earn her own money.

Alice Schoch was born into a farmer’s family in 1896. Her aunt had an apron and blouse factory, which is where Alice learned to sew. Later on she also attended a young women’s school where she gained more theoretical knowledge. When her aunt died, she would have liked to take the factory over, but her brother, who had been fostered by the aunt, inherited it. So Alice saved money for a year to buy a sewing machine and then started to make aprons herself.

In 1921, at the age of 25, Alice married Albert Kriemler. When he was traveling across the country as a shoe cream salesman, he took his wife’s apron collection with him to sell. They proved to be a success, and soon Alice needed help to fill the orders. She established a small production space for eight seamstresses and two cutters on the ground floor of her house in St. Gallen. Albert would take orders on his travels and his wife and her seamstresses would sew the aprons the following week. In 1922, a few months after the birth of her first son, the company A. Kriemler-Schoch (Akris in short) was registered as a single ownership company. Production continued to grow and aprons of every kind were made, whether they were for housewives, factory workers or waitress’s white aprons trimmed with fine St. Gallen lace.

By the 1930s, jumper dresses and simple cotton dresses for farmer’s wives were added, and a little later blouses. Alice would also take personal commissions to make dresses for private clients. In 1935, the first order from the Globus department store followed. After having moved the factory to larger premises and the family to an apartment in the same building in 1933, the family moved again in 1939, this time to a large villa and a factory building next to it.

Despite rationing of fabrics and other materials, the company remained in production during WWII. Max, the elder son, helped at the office and then took a job with a fabric company, whilst the younger son Ernst was apprenticed to a tailor. In 1944, Albert died unexpectedly of a heart attack, so Max entered the company to help his mother. He took over his father’s work, traveling to sell their clothes. This was supposed to be a temporary solution, but in the end, Max stayed and took care of the business side of things.

In 1949, proprietorship of the company was officially transferred to Max, though Alice remained in her position within the company and looked after the apron production, which remained especially close to her heart. She worked tirelessly, keeping an eye on the high quality of work she demanded and a close eye on her workers, though she always had an open ear if they had problems. Nieces and sisters-in-law were given jobs in the company, and even Ernst’s former master was employed as a salesman. When she did allow herself some time off, Alice enjoyed hiking, swimming and skiing as well as social life in local clubs or attending the occasional fashion show in Zurich.

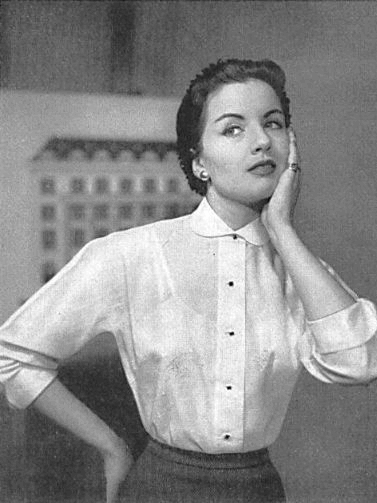

Akris blouse, 1953. From Swiss Textiles, English edition.

By the 1950s, Akris had diversified into all kinds of women’s garments, and they were known for the quality of their products. Cocktail dresses were introduced by 1953, and even bathing suits were made for a short time. The trademark for the company name “Akris” and its logo (which Max had designed as a student in 1939) was registered in 1960. Ernst had joined the company for a while too, but moved away to marry and take over his in-laws’ haberdashery. By the late 50s, Max had also married, and his first son Albert was born in 1959. Max’s wife Ute entered into the factory business for a while to learn how aprons and blouses were made.

The production of aprons was kept up as long as possible, but it had been getting harder to keep their production costs low enough to remain competitive, especially with the high quality work that went into them and for which they were known. Since the early 40s, Swiss clothing manufacturers had started to move production, especially of lower-priced items, to more rural regions where they could pay lower wages (akin to today’s fashion companies moving production to low-wage countries). Akris too made that move, and from 1946 to 1966 they operated a small apron factory in Kriessern, a small town in eastern Switzerland, where most of the income came from farms and possibilities for young unmarried women to earn money were scarce. Fabrics were cut at the main factory in St. Gallen and then sent to be sewn up in Kriessern. Standards for the work were high, and the aprons had to be perfectly sewn. Each was checked when the finished items were sent back. Alice herself visited the small factory regularly and invited her “girls” to company Christmas parties and her son’s wedding.

Another move was to buy up fabric remnants from well-known manufacturers such as Mettler or Fischbacher and use these dress fabrics for aprons, which was a novelty. These slightly more expensive aprons were even sold to Harrod’s in London. Production of other garments also started to be outsourced to various factories within Switzerland during the 1950s. The apron business did not get easier—it was harder to find workers to make them and interest in them by customers started to wane in the 1960s.

All the same, Akris continued to grow, and in the late 60s/early 70s they started to produce lines for Saint Clair, Ted Lapidus and Givenchy. In 1970, Akris provided the uniforms for the waitresses at the Swiss pavilion at the universal exhibition in Osaka, Japan. In 1971, Alice noted in her diary that hot pants were being made.

Max and his family lived with Alice in a separate apartment in the house built to replace the old villa. Up to the last year of her life, Alice continued to be involved in the company as well as looking after her grandchildren—also sewing for herself and her family and even making a silk dress for her housekeeper. Alice Kriemler-Schoch died in 1972 at age 76. Her legacy was a thriving fashion company that continued to grow.

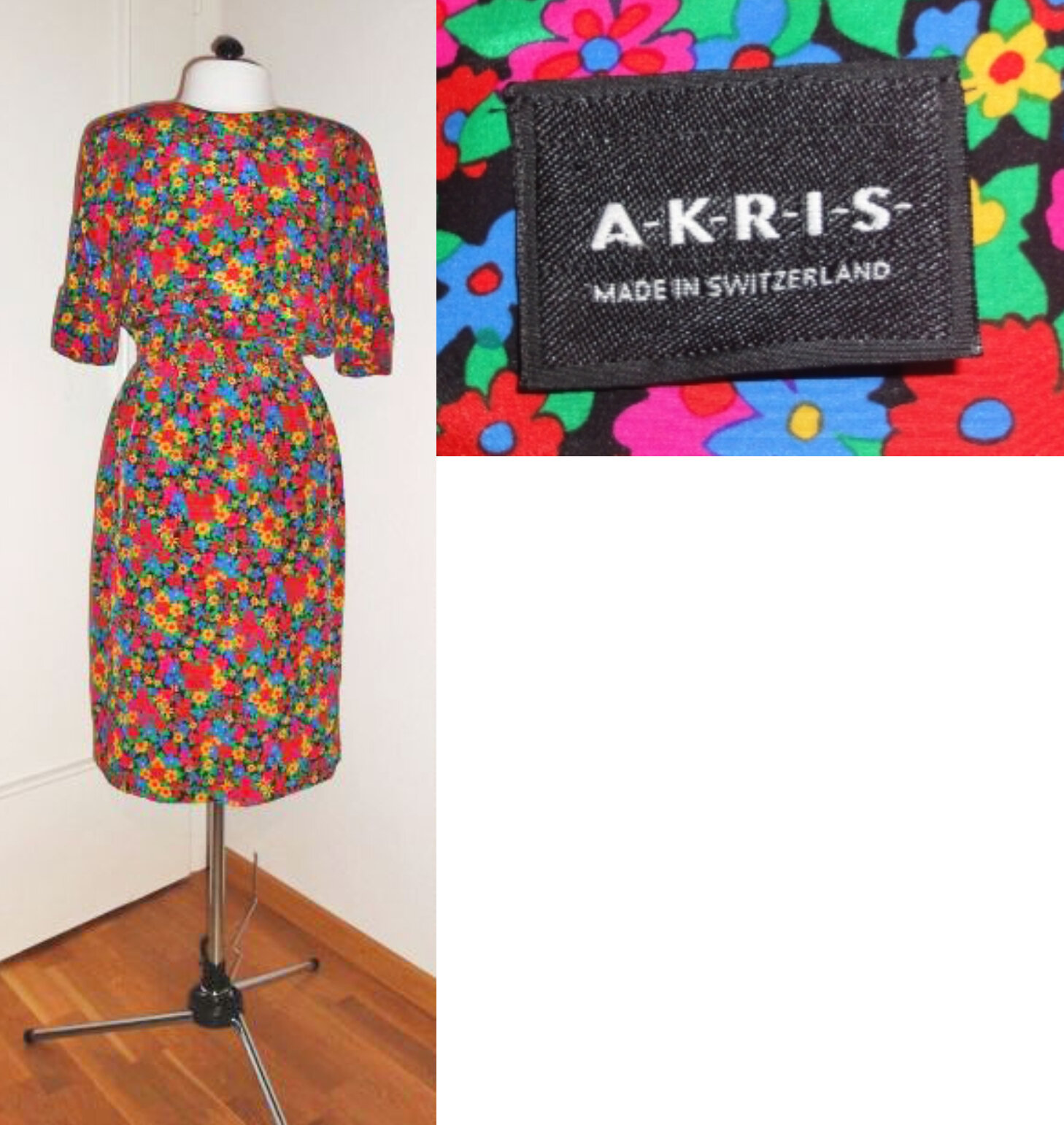

Akris silk dress, 1980s.

In 1980, Albert Kriemler joined the company, after having postponed his fashion studies in Paris and a planned apprenticeship at Givenchy, because Max’s right-hand man had died. He soon became the creative director, which he still is today. His younger brother Peter joined the company in 1987 and is responsible for the business side of things. Thanks to his imaginative flair and demand for uncompromising quality, Akris has become more prestigious under Albert’s creative direction. Akris Punto, a less expensive line, was introduced in 1995.

In 2000, Akris was admitted into the “Chambre Syndicale”, the governing body of the French fashion industry, but only staged their first show during Paris Fashion Week in 2004 because they had wanted to get a place on one of the four most important days. Max Kriemler died at age 95 in 2017. In the 2000s, Akris had become one of the world’s fastest-growing designer brands and was a top seller at stores such as Bergdorf Goodman and Neiman Marcus. A lot of their success is due to word of mouth instead of expensive advertising, and unlike other luxury brands, they do not rely on big logos and have not branched out into fragrances, as well as not licensing their name. Even handbags are limited to their horsehair AI bags. Among their signature items are the jackets made of double-faced cashmere, fine St. Gallen lace and digital photo prints. And of course, there will always be perfect tailoring. The company is still in the family’s hands and the headquarters are still at the same address in St. Gallen that Akris had moved to in 1939. Production is still centered in Switzerland as well.

Crossair uniform by Akris. Images courtesy of Cliff Muskiet, http://uniformfreak.com

From 2000 until 2002, the uniform design worn by the flight attendants of the now defunct Swiss regional airline Crossair was by Akris. They submitted their designs when Crossair announced a contest for a new uniform design. In a newspaper article, Albert Kriemler, a frequent traveler himself, admitted that he didn’t like uniforms as such, finding airline uniforms to be old-fashioned. Unspeakably bad is what he thought of the uniforms worn by flight attendants of other regional airlines at the time (Crossair competitor Tyrolean Airways dressed their crews in dirndls). He set out to create a uniform that was functional, modern and chic. Research into what flight attendants wanted was done by interviewing crew members of different airlines. One result of that research was a twinset—planes are often freezing cold inside in early mornings, yet flight attendants are supposed to be wearing nothing more than a thin blouse inside. The hat was either a simple beret or a chic fedora style, and instead of a traditional handbag, there was a square-shaped blue leather backpack.

While Akris today moves in very different fashion circles than during Alice’s time, her legacy still shines through. There is of course the quality and attention to detail that was so important to her, but upon looking back on the clothes made during her time, Albert Kriemler also said that they were chic, classy designs, never staid or old-fashioned, and even her aprons had bust darts, which no one else did at the time, but which meant they had a more flattering fit. And there are vintage lace and embroideries that were kept and are being reused. For one blouse design, a lace motif from the 1950s was reproduced by Forster Rohner (another long-standing fabric company from St. Gallen that today produces exquisite fabrics for haute couture houses).

Wool Blouse and skirt worn by Elisabeth Kopp. Akris, 1984. Swiss National Museum, inv. LM-91201.1-3. www.landesmuseum.ch

Coat worn by Doris Leuthard, Akris, 2016. Swiss National Museum, inv. LM-177470. www.landesmuseum.ch

Akris has also become a go-to for many prominent women, from film stars to politicians. In 1984, Elisabeth Kopp, the first female Federal Councillor of Switzerland, wore an ensemble by Akris for her swearing in—the photos of the event have become iconic, though they are all in black and white so unfortunately do not convey the bright colours of the ensemble. No less iconic was the Akris coat that Federal Councillor Doris Leuthard wore to the opening of the new Gotthard base train tunnel (the world’s longest train tunnel) in 2016. Condoleezza Rice wears Akris, other celebrity fans are Princess Charlène of Monaco, Angelina Jolie, Susan Sarandon, Amal Clooney and Nicole Kidman.

Swiss author Jolanda Spirig has written an excellent book about the seamstresses in Kriessern and Alice Kriemler-Schoch, called Schürzennäherinnen. It provides an interesting insight into young women’s lives in the 1940s and 50s, as well as into Alice Kriemler-Schoch’s life.

Written by Karin Marty, owner of Willynillyart, online shop for vintage sewing patterns.

Alice Kriemler-Schoch in the 1950s.