Fashion-related shows are held regularly at Zurich’s Museum für Gestaltung. Thanks to the Swiss Textile Collection, I was able to see the latest one in a private (only for our group) guided after-hours tour with the curator, Andres Janser.

Hubert was a prolific designer but seems to have been forgotten a bit. He appears to have been well known in the 1950s, when he was designing for major Hollywood films as well as commercial ventures in Switzerland, and he was frequently mentioned in fashion magazines.

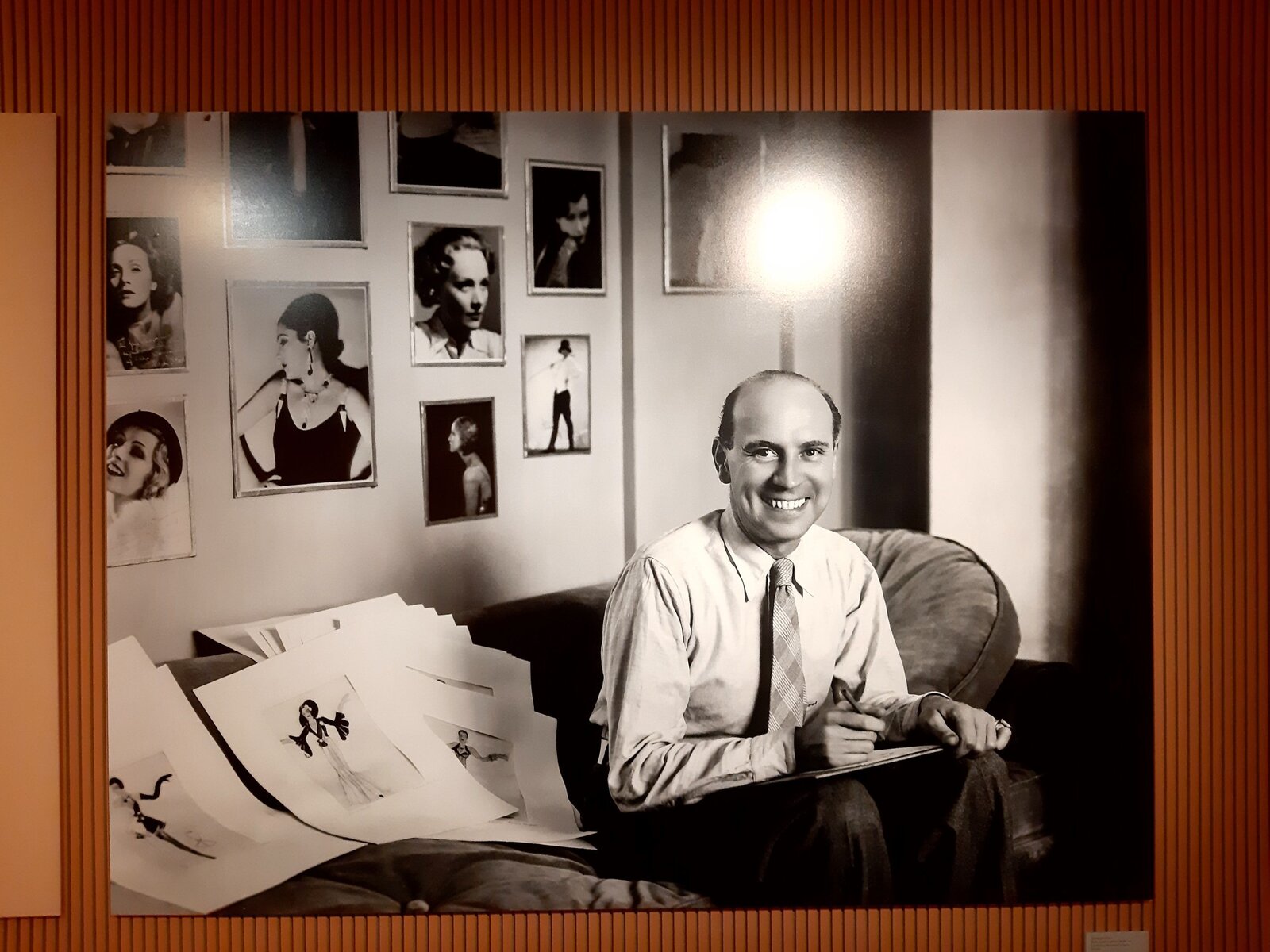

So, who was René Hubert? He was born in Frauenfeld, Switzerland, which is near St. Gallen; a career as an embroidery designer in one of the many lace/embroidery companies of St. Gallen was what he trained for first. He never trained as a tailor or dressmaker, but he had an eye for design. In the 1920s, he went to Paris for further training, where he was introduced to the music hall scene and started designing costumes for shows. By sheer good fortune, he landed the job of designing costumes for the 1924 Gloria Swanson movie, Madame Sans-Gène, which was filmed in Europe. Unfortunately, this silent film has not survived, but there are photos, some of which were in the museum show. Hubert began costuming Gloria Swanson (in real life as well as for movies) and many other stars in Hollywood films. He came back to Europe in between Hollywood engagements and worked on stage musicals and film in London (science fiction costumes for Things to Come —very reminiscent of Star Trek—and Fire over England), Paris, and Berlin. In 1939, he designed clothes for a fashion revue at the Swiss national exhibition, then spent the 1940s in Hollywood working for 20th Century Fox, dressing Marlene Dietrich in The Flame of New Orleans and Vivien Leigh in That Hamilton Woman, among others.

He returned to Switzerland in the 1950s and designed clothes for the Jelmoli department store, fabrics and clothes for Stoffel (about which I recently wrote), and his own range of hankies and scarves. René Hubert went back to film costuming for a few more films, not least because he wanted to try his hand with the new colour film processes, and with Cinemascope. He costumed a historical epic in Cinemascope, and he also worked on Anastasia with Ingrid Bergman. (Fun fact: Balenciaga’s atelier in Paris was used for costume fittings—but of course this was kept secret.) He received Oscar nominations for best costume for Désirée and The Visit. And if that wasn’t a full career already, from 1951 to 1966 Hubert also worked for Swissair! During the introduction of jet aircraft, he was in charge of cabin interior design and three uniform collections. The famous “Swissair blue” of these uniforms is also credited to Hubert. He designed everything, including a fur hat for cold destinations (which wasn’t made) and a light “tropical dress” for warm destinations—which was made.

The museum’s website has a short trailer, which gives a nice overview of the exhibition: René Hubert: The Clothes Make the Star

I enjoyed this immensely, not just the exhibition because it ticked off so many of my interests—fashion, classic Hollywood films, and airline history—but also because of the incredibly knowledgeable and enthusiastic commentary from the curator. It was a relatively small exhibition, and as the transport costs have risen so much due to the pandemic, they could not show as many costumes as they would have liked. Still, it was a fantastic experience!

To go with the exhibition, the Filmpodium, a small art house cinema owned by the city, was showing a series of films with costumes by René Hubert. I went to see Désirée, which I hadn’t seen before, but by chance I had read the book (a worldwide bestseller in the 1950s) a few years ago. As for the film, it was most of all entertaining. Historically correct it is not, and neither are the costumes—the shapes may be roughly right, but the colours and fabrics certainly aren’t. However, they’re elaborate, and there are a lot of them. Hats off to any costume designer who can pull this off!

Written by Karin Marty, owner of Willynillyart, online shop for vintage sewing patterns.