See shoes from VFG members on Etsy (paid link)

THE 19th CENTURY – Modesty and Technology

Nature may dictate height but the shoe designer is more than capable of manipulating it. This was never more obvious than immediately following the French Revolution (1792) when shoe heels all but disappeared. Their demise was motivated by politics and the desire to suggest that everyone was born on the same level.

Heels first returned on male footwear when in the late 1810s a new fashion emerged. Trousers were anchored with stirrup straps underneath the foot, which displaced the older knee-length breeches. The heel was an additional aid in keeping the pant strap in place.

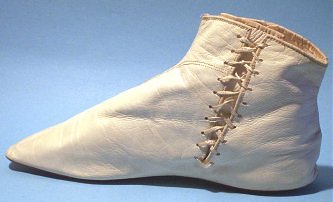

By 1830, the square toe had come into fashion. An efficient industry manufacturing women’s silk and kid footwear was developed in France in the 1830s using piecemeal workers. Their shoes were created for speculative sale in shops. The shoes were narrow but their construction was light and forgiving, allowing the wearer’s foot to splay over the edges of the sole. Sturdier leather shoes and boots (for both men and women) were still made to order by a local shoemaker.

By the 1850s boots became a positive necessity for women in order to retain modesty. The fashion was for steel-framed crinoline hoops that tended to swing when walking. Boots prevented exposing the female ankle, protecting her modesty.

Long, full skirts predominated after 1840 resulting in a plethora of plain and uninteresting footwear. Even so, some shoes were made that were worked in colourful embroideries; the decoration usually created with machine-sewn chain stitching.

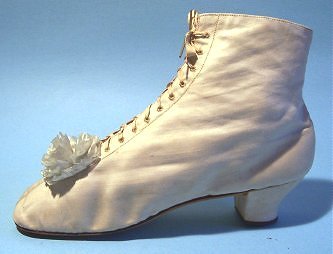

Small heels were re-introduced to women’s footwear mid-century, although they weren’t standard until the 1870s when bustled skirts became the mode. The high heel was causal in protruding the posterior, which in turn enhanced the bustle’s primary objective! By the mid 1870s “Louis” (hourglass-shaped) heels of two inches were not uncommon.

Revivals of 18th century-style bows and buckles became fashionable additions from 1863 when the “Fenelon” bow (a multi-looped bow) first appeared on the toes of shoes. Skirt fronts fell close to the body in the 1870s and 1880s, therefore the toes and vamps (forepart) of shoes and boots became visible. As a result shoes took on more detail in the form of punch-work and embroidery, or inserts and cutouts. Similarly, button closures became very popular. These were thought a neat, yet more attractive way of closing boots than laces or elastic inserts.

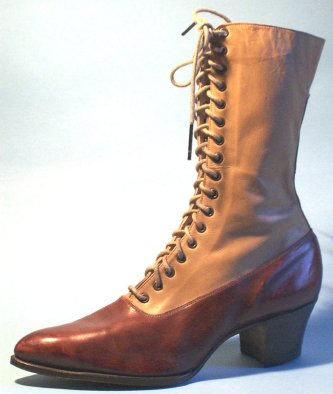

In the 1880s the United States began manufacturing footwear, using technology it had been developing for around 20 years. Innovations in production comprised lasting (shaping wooden shoe forms), cutting, sewing, beading, and sizing footwear. This meant that sturdy, fashionable, fitted footwear could be produced for a fraction of the cost of custom-made.

While this allowed many people to afford better quality shoes for less money, it also set the stage for “couturier” shoemakers to cater to the elite. Paris-based shoemaker Francois Pinet is generally credited with being the first important “bottier.” His costly made-to-order boots and shoes were the perfect ornamentation to a Worth or Redfern gown, whilst at the same time excelling in quality construction and fit.

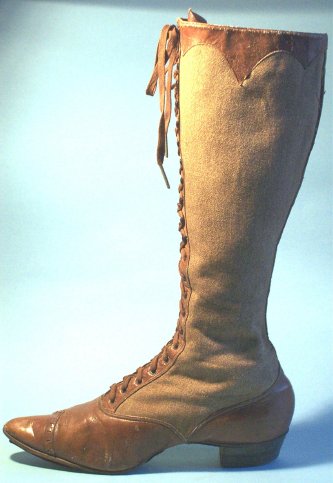

Boots continued to dominate shoes as daywear as the century drew to its close. New styles were introduced to accommodate the changing needs of the active woman. Sporty styles in canvas with rubber soles or low-heeled leather boots with wool shafts appeared. They were designed for such activities as playing lawn games or partaking in the biggest and hottest craze of the 1890s – bicycling!

THE 20th CENTURY – The Shoe Revealed!

By 1914, skirt lengths had begun to shorten and were sometimes cut in such a way as to make the ankle clearly visible. Boots started to fall from favour for evening wear with some exceptions. These were “Grecian” or “Tango” boots with decorative cutouts or strap arrangements.

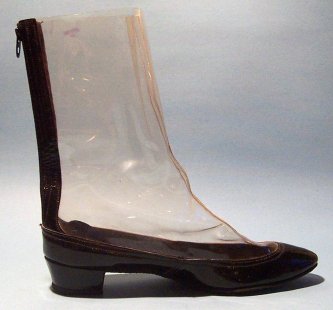

For modesty reasons, the boot held on to its popularity for daywear until the early 1920s. Their days were numbered when skirts rose to mid shin. Wearing boots left an unsightly gap between the top of the boot and the hem of the skirt. The only remedy for this was to wear shoes, which made visible the pleasing contours of the lower leg. At this point boots virtually disappeared, their fate being to languish in fashion wilderness (their only outing being as galoshes in foul weather) until the mid 1960s.

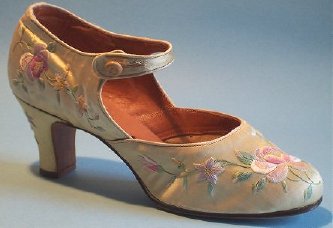

Ironically from the 1920s to the 1960s, while women were making huge strides in their quest for liberation, their footwear became more debilitating. The shoe, which was now in full view, became an integral part of the fashion wardrobe. Shoes were now being made in colourful leathers and decorations. High heels tightened the calf muscle and made the ankle appear slimmer, creating a more shapely illusion, which women eagerly latched on to. Instep straps on shoes eventually fell from favour in the late 1920s. Their crime was to cut the length of the foot.

The long-absent classical sandal re-appeared in the early 1930s for beach and eventually eveningwear. Smart, high-heeled laced shoes made good alternatives to plain pumps for a sporty look and two-toned spectator shoes were suitable for summer weather. In 1939, open toe, sling-back pumps were shown for the first time. This was amidst much complaining from the ‘fashionables’ because the reinforced toes and heels of stockings were not exactly appealing in this shoe style.

Numerous shoe designers entered the scene in the 1930s, most notably Henry Rayne and Andre Perugia. They created shoe collections under their own labels and also supplied couturier collections.

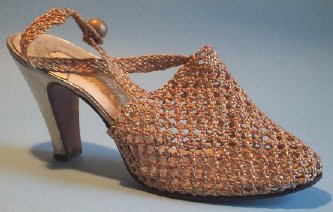

In 1937, Italian designer Ferragamo was inspired by the Italian Renaissance and re-introduced the Chopine, a tall platform shoe style. Fascist Italy was at war with Abyssinia and was experiencing shortages so Ferragamo substituted other materials for leather. He used cork and wood for platform soles and wove new materials, like cellophane for straps and vamps. Successful as a novelty at first, these non-leather shoes were important in continental Europe for the duration of World War II when all available sturdy leather was requisitioned for army gear and machinery belts for wartime factories.

By 1941 platform soles appeared in North American footwear, small at first. They elevated a woman’s height and, when combined with padded shouldered suits, gave them an imposing stature. This suited the times for they were tending the home front while their men were at war. Wedge heels were popular too. They not only gave height but also supplied the sturdiness of a flat-soled shoe. By the end of the war platforms had increased to four or five inches in height. However, the style was not considered attractive by all women, particularly tall women who yearned to look petite.

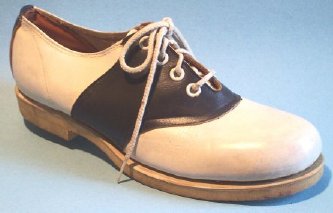

Sturdy laced oxfords made of durable leather were rationed but lasted for years with proper care. The endurable plain pump with Cuban heel and round toe provided a dressier style for the war years.

Following the Second World War fashion footwear, just like clothing, could no longer be contained to one look. A multitude of designers fed society’s hunger for different styles to suit time of day, social function, utility, looks, and audiences

“Teenager” was a new term coined in the post war world. It recognized a matchless sector of society. Anti-fashions donned by various groups were used to identify a unique culture, be it left bank Parisian intellectuals or rowdy English street thugs.

Dior’s 1947 “New Look” collection was the catalyst that heralded in a softer, feminine ideal. Chunky platform-soled shoes were slowly phased out to make way for the revival of the high-heeled pump. This time it relied less on ornament, and more on architecture. The 1950s pump and sandal gradually slimmed their heels, especially in Europe where the thin Italian stiletto heel was first shown on fashion runways in 1954. The pointed toe was paired up with the stiletto heel in 1957. This created a shoe that enhanced and beautified the foot yet impaired it unrelentingly. Shoe designers like Roger Vivier and Beth Levine made the most of its attributes in their versions.

However, the stiletto had practicality problems. Driving was tricky and sidewalk grilles were deadly. The wearer was pretty deadly too of course. Men were more afraid than at any other time in shoe history, especially on the dance floor. Museum curators were suicidal at precious floors pock marked by tiny weapon-like heels. Worst of all, makers of galoshes could not find a suitable rubber overshoe that was not pierced by the foot-borne spear upon its first wearing

Various designers toyed with boot designs, including Charles Jourdan and Pierre Cardin. But it was Courreges in 1964 that is credited with the return of the boot. It was the revolutionarily opposite of the fashionable shoe of the day. A square toed, low-heeled boot cut just above the ankle, it found success with the younger generation. Shoes too took on the new silhouette, but it was a slow transition from the old style. Mature women preferred the more sophisticated pointed toe stiletto albeit by 1967 the low-heeled shoe had won out.

By 1970 the low heel was on the rise again. Heels were either blocky square shapes or tall and straight. The toe rounded gradually to become more almond shaped throughout the decade. In 1971 wedge heels and platform soles returned as options. This time they found favour with liberated women who enjoyed the empowering height. The platform’s popularity peaked in about 1974 then declined, disappearing completely by 1980. Knee high boots were essential elements of the winter wardrobe, in shiny vinyl at the beginning of the decade and earth toned leathers and suedes by its end.

The Hippie movement of the late 1960s brought a new image to footwear. Themed as “back to nature” it first included the popular rise of simple sandals; leading in turn to “health-conscious” styles to include negative heeled oxfords and athletic runners. Attractiveness was not paramount in the consideration of casual shoe styles but comfort, fit and foot health was. An oxymoronic footwear fashion twist emerged as the 1970’s ended. A woman could wear a pair of Anne Kelso’s crepe soled, negative-heeled “Earth” shoes in the office and a pair of barely-there, strappy Maude Frizon, spike-heeled evening sandals to the disco.

In the collections of designers like Andre Pfister, colour and surface embellishment abounded on 1980s footwear. The stiletto heel returned but was only one of many heels that were equally fashionable. These included low slanted heels and upside down, triangular-shaped heels. Indigenous styles of boots such as cowboy and Cossack boots found favour alongside sleek knee-high fashion styles.

With the 1990s came a series of revivals. Late 1960s styled low heeled, square-toed shoes were available alongside 1970s style platforms, like those made popular in John Fluevog’s collections. Curvy hourglass heeled shoes from Stuart Weitzman and Peter Fox revived early 1920s styled footwear. Casual chic returned in updated classics like Patrick Cox’s revivals of the Hush Puppy suede loafer. Subculture boot modes like laced fetish boots in black vinyl were available at the same time as punk style Doc Marten combat boots. Athletic footwear continued to carve a huge niche out of the footwear industry, seceding from influences of high fashion and creating its own vocabulary of style.

It is not uncommon these days to refer to ones shoes as my “Blahniks”, or my “Clegeries” rather than “my pink pumps” or “black mules”. Today, fashion footwear is less about being “au courante” and more about the design, the designer and recognition.

Written by Jonathan Walford/Kickshaw Productions All Photos courtesy Kickshaw Productions