Wit, innovation, transformation, freedom, defiance, chic—and shock. How many of us would dare to take fashion inspiration from the most iconoclastic of designers?

Elsa Schiaparelli was born in Rome in 1890. A defiant girl from the start, she ran away from home at the age of six only to be found several days later, at the head of a parade. When she was 21, Schiaparelli wrote a book of erotic poetry, shocking her aristocratic parents who promptly sent her to a convent. When she waged a hunger strike they were forced to bring her back home.

The youngest in this family portrait from 1892

Repeatedly told by her mother that her older sister was a beauty and that she was homely, as a girl Schiaparelli once tried to plant flower seeds in her nose, mouth and ears, presciently imagining she could make herself blossom into a beauty. She gradually found love and admiration through the creation of beauty.

After a hasty, early marriage fell apart in 1914, Schiaparelli began to discover her life’s work. Her marriage had taken her to New York, and with the help of connected friends, she relocated to Paris where she became associated with artists and made her way into the domain of fashion.

Schiaparelli was at her height in the inter-war years, an equal to her rival Coco Chanel, and most of these style elements for which she is known are tied to that time.

Collaborations with artists

Schiaparelli was greatly influenced by the artists whom she considered her soulmates. First by the Dadaists, then even more profoundly by the Surrealists, her friends and collaborators included Jean Cocteau, Christian Bérard, René Magritte, Alberto Giacometti and most especially Salvador Dalí.

Coat, 1937 (photo from Architectural Digest, September 1988) and Evening suit jacket, 1937 (Metropolitan Museum of Art), both with embellishments designed by Jean Cocteau; Wallis Simpson wearing the Schiaparelli/Dalí-collaboration lobster dress, 1937 (photo by Cecil Beaton); The famous shoe hat worn by Gala Dalí, 1937—another Schiaparelli/Dalí collaboration (Ullstein bild, photo by André Caillet); Giacometti for Schiaparelli bracelet, 1935 (Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris/Jean Tholance).

Surrealism

The dream worlds of the Surrealists particularly appealed to Elsa Schiaparelli, and her creations reflected those dreams tinged with her own iconic wit.

Lobster hat attributed to Schiaparelli, 1939 (photo source unknown)—lobsters were one of Dalí’s favorite subjects and Schiap took to them equally; Models wearing Schiaparelli in a surreal landscape, 1936 (photo by André Durst); The iconic Tears Dress in collaboration with Dalí, 1938 (Victoria & Albert Museum, Gift of Miss Ruth Ford); Glasses, 1951 (photo by Gordon Parks).

Trompe l’oeil

Elsa Schiaparelli first made her mark on the fashion world in 1927 with boxy sweaters knit in a special double layered stitch to keep them from losing their shape—and most importantly featuring trompe l’oeil in their designs. These caused an immediate sensation and were the basis for her opening her atelier, even if just in a garret to start. By 1935, her atelier was the 98-room salon and work studios at 21 Place Vendôme, which was christened the Schiap Shop. She had had no formal training.

Trompe l’oeil sweaters, 1927 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Mme Elsa Schiaparelli), c. 1930s (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Miss Neale Mergentime), 1928 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Vera White); Woodgrain dress, 1938 (The Goldstein Museum of Design); Fabric sample for Schiaparelli, 1936 (Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris/Jean Tholance); Silk gloves decorated with plastic discs reminiscent of chain mail worn by Millicent Rogers, 1935-1940 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum).

Wit

Surrealism, trompe l’oeil… The humor in Schiaparelli’s work is undeniable. That lobster dress? There are parsley sprigs scattered near the hem. Gloves have manicures, pockets have lips.

Peek-a-boo hat, 1949 (Mauritius Images); Pair of ostrich clips by Jean Schlumberger for Schiaparelli’s Circus Collection, 1938 (sold on 1stdibs); Cane purse, c. 1950s (sold by Whitaker Auction Co.); Schiaparelli Sleeping perfume bottle and suede case, 1938, part of the Circus Collection (Perfume Bottles Auction); Gloves, winter 1936-1937 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Mme Elsa Schiaparelli); Salvador Dalí for Schiaparelli telephone dial compact, fall 1935 (sold by 1stdibs); Model in suit and a whimsical cap with braid by Schiaparelli, outside Schiaparelli’s store, Paris, 1951 (Photo by Regina Relang).

Freedom

Before evening wear, Schiaparelli made her name in sportswear and she never lost sight of practicality in her design. She created a wardrobe of mix-and-match, easy-care separates for her own travel. She dressed the English pilot Amy Mollison in a handsome, work-worthy outfit. In 1931, she put the tennis star Lilí Álvarez in a split skirt, shocking the staid Wimbledon crowd.

Schiaparelli skiing in St. Moritz with her daughter Gogo, 1934 (Rex Features); Aviatrix Amy Mollison in Schiaparelli newspaper-print blouse, 1936 (Maison Schiaparelli); Jupe-culottes worn by Lilí Álvarez at Wimbledon, 1931 (Maison Schiaparelli).

Transformation

Struggling with the curse of being told she was unattractive from early on, Schiaparelli seemed to seek redemption through fashion, both in beautifying herself and through the glorification of the ordinary in her design.

As a girl, Schiaparelli was troubled by the moles on her face, but her uncle, a noted astronomer, said they outlined the Big Dipper, which was good fortune. Schiaparelli wearing her own designs (Wikipedia); The Big Dipper became her symbol and she commissioned a diamond pin of it. Dalí and Schiaparelli, c. 1949 (Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí); The famous Horst photo of Schiaparelli in an oval mirror reflects a wary introvert, 1937.

Patchwork-print evening ensemble, 1936 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Esmé O’Brien Hammond); Simple black dinner dress with elaborate jeweled sleeves, 1938 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Mme Elsa Schiaparelli).

Butterflies

Not just a favorite symbol of the Surrealists, but surely of personal significance to a woman who wanted to transform her appearance, butterflies are a recurrent theme in Schiaparelli’s work. Sometimes they are unfettered, as butterfly button-like decorations seem to take flight off a jacket, other times caught, as a black netting over-dress envelopes a butterfly-printed dress beneath.

Dress and over-dress/jacket, 1937 (photo by André Durst); Jacket with butterfly buttons (Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris/Jean Tholance).

Embellishment

Playing a very important role in many of Schiaparelli’s 1930s creations was the embroidery realized by the House of Lesage. In some cases it nearly covered the fabric on which it was stitched, yet always heightened the design of the garment without overwhelming it. With Schiaparelli and Lesage one feels the sense of great dancers in a pas de deux, their arts completely intertwined.

Zodiac Collection evening jacket, 1939 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum; Gift of Mrs. Anthony V. Lynch); Evening jacket, Autumn/Winter 1937/38 (National Museums of Scotland); Bolero, c. 1948 (Kerry Taylor Auctions).

Novelty buttons

Somewhere between fastener and jewelry, Schiaparelli’s buttons very often were set free from their usual roles and wended their way diagonally down the front of a jacket or floated onto a hat. The placement, the size and most of all the themes (everything from snails to shell casings) were deviantly inventive.

Trapeze artist buttons on a Circus Collection jacket, 1938 (Victoria & Albert Museum, Gift of Miss Ruth Ford); Cicada button on a Pagan Collection jacket, 1938 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. J.R. Keagy), Lyre and piano buttons from the Music Collection, 1939 (Both Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum; Gift of Arturo and Paul Peralta-Ramos).

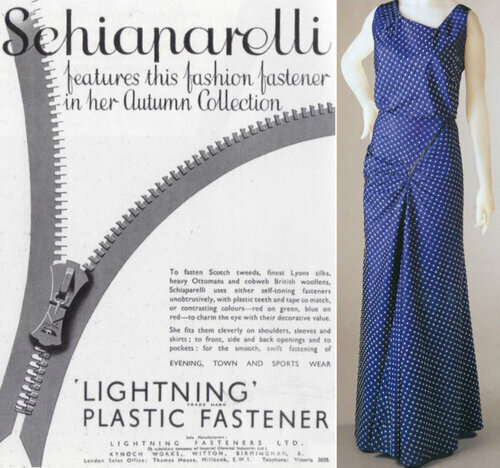

The ‘Lightning Fastener’

In another technically inventive inspiration, Schiaparelli took to the zipper (the Lightning Fastener) at the vanguard of its popular use. Instead of keeping its practicality hidden, she glorified it in her designs, using it as a jolting focal point.

Lightning fastener advertisement, 1935; Evening gown with angled zipper, 1935 (Drexel Historic Costume Collection).

Unusual materials

Schiaparelli upended the expected in fabric use, using day fabrics for evening and evening fabrics for daywear. Her couture garments combined even suede with lace. She experimented with new man-made fabrics, including a glass-like Rhodophane (which proved impractically fragile). Her wit extended to prints featuring seed packets, carousel animals and her own press clippings.

Rhodophane ‘glass’ cape, 1935 (photo by André Durst); Evening blouse and bag of silk printed with the number of ration coupons required for each of the garments pictured, 1940-45 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Julia B. Henry); Seed packet-print cotton dress, 1939-41 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum; Gift of Millicent Huttleston Rogers); Plastic belt painted with pink stars, c. 1938 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum; Gift of Millicent Huttleston Rogers).

The evening suit

So many of Schiaparelli’s 1930s creations were in the form of suits, most notably and inventively her evening suits. The dresses, sleek and baring gowns, were relatively unadorned, while their jacket mates could be ornately embellished.

Her other advancements include a wrap dress, a backless swimsuit, a built-in bra, culottes/trousers and folding glasses.

Evening jacket, winter 1937–38 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Enid Rubin, in memory of her mother, Margaret L. Kastor); Pagan Collection jacket, winter 1938 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. J.R. Keagy); Schiaparelli ensemble in front of Brancusi’s “Bird in Space” sculpture, photo by Louise Dahl-Wolfe); Dinner jacket, spring 1940. Worn by Schiaparelli on her American lecture tour in 1940, this jacket features “cash and carry” pockets designed to replace a handbag. (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Mme Elsa Schiaparelli).

Design themes

Themes often ran through seasonal collections, giving direction not only to the designs and embellishments, but to the performance-art theatrics of Schiaparelli’s fashion shows.

The Music Collection of fall 1939 included music boxes in belt buckles and on hats, colorfully sparkling embroidered musical notation, and buttons shaped like instruments.

Evening dress, 1939 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum; Gift of Millicent Huttleston Rogers); Evening gloves, 1939 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Mme Elsa Schiaparelli); Evening belt, 1939 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum; Gift of Millicent Huttleston Rogers); Evening gloves, 1939 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum; Costume Collection Fund); Evening dress, 1939 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Mme Elsa Schiaparelli).

The Zodiac collection of winter 1938-39 was an homage not only to astronomy, but to the Sun King Louis XIV, and to Apollo.

Evening belt, 1938-39 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum; Gift of Arturo and Paul Peralta-Ramos); Evening cape, 1938-39 (Kyoto Costume Institute); Evening blouse, 1938–39 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum; Gift of Arturo and Paul Peralta-Ramos); ‘Phoebus’ cape, winter 1938-39 (Palais Galliera, Musée de la Mode de la Ville de Paris, Gift of the children and grandchildren of Daisy Fellowes); Zodiac necklace, Jean Clement for Schiaparelli, 1938-39 (The Billyboy Paris Collection).

In her extraordinarily prolific 1938, Schiaparelli produced not only the Zodiac collection but the Circus and Pagan collections. The Commedia del’Arte came in 1939.

“Le Cirque”, 1938 by Christian Bérard; Evening dress, 1938 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Mme Elsa Schiaparelli); Evening ensemble jacket detail, 1938 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum; Gift of Mrs. V. D. Crisp); Evening jacket, 1938 (Victoria & Albert Museum, Gift of Miss Ruth Ford); Pin attributed to Jean Schlumberger for Schiaparelli, 1938 (1stDibs); Evening gloves, 1938 (Victoria & Albert Museum, Gift of Miss Ruth Ford).

Evening dress, 1938 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Mme Elsa Schiaparelli); Hat, 1938 (Victoria & Albert Museum, Gift of Lady Alexandra Trevor-Roper); Evening jacket, part of suit, 1938 (Victoria & Albert Museum, Gift of Lady Alexandra Trevor-Roper); Choker, 1938 (Victoria & Albert Museum, Gift of Miss Ruth Ford); Detail of evening dress, 1938 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum; Gift of Millicent Huttleston Rogers); Necklace, 1938 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum; Gift of Arturo and Paul Peralta-Ramos).

Highlights from the Commedia del’Arte collection, 1939 (photo by Erwin Blumenfeld); Coat, 1939 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Ruth Ford); Dinner jacket, 1939 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Mme Elsa Schiaparelli); Harlequin by Jean Schlumberger, 1939 (1stDibs); Dinner jacket, 1939 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Mme Elsa Schiaparelli).

Chic noir

Edgy black was a Schiaparelli speciality, as brazenly exemplified by the Skeleton Dress from 1938. Made of fine, matte silk in a clingy cut, the ‘bones’ of the dress are formed by normally delicate trapunto quilting thickly stuffed with cotton wadding.

Her edginess carried into a sort of eek chic, with a brilliant array of realistic bugs crawling around an innovative clear plastic collar (as if directly on the wearer’s skin), and fine silk printed with what look like gaping wounds used for the Tears Dress.

Outfit and veil hat, 1949 (photo by François Baudot); Necklace by Jean Clemént for Schiaparelli, 1938 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum; Gift of Arturo and Paul Peralta-Ramos); ‘The Skeleton Dress’, 1938 (Victoria & Albert Museum, Gift of Miss Ruth Ford); Detail of ‘The Tears Dress’, showing both the printed silk of the dress and the 3-D effect used for its companion hood, 1938 (Victoria & Albert Museum, Gift of Miss Ruth Ford).

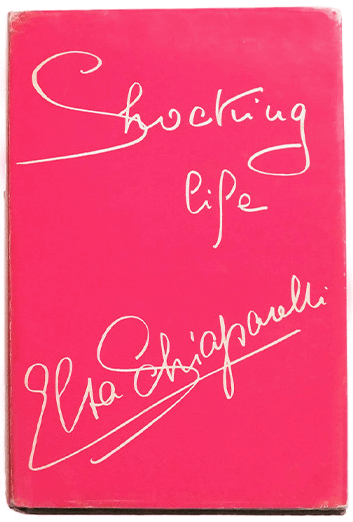

Shocking pink

Famously described as “…an aggressive, brawling, warrior pink” by Yves Saint Laurent, this vibrant color was the non-sweet signature of the designer, giving name to her most famous perfume, color to her packaging, and finding its way into her fashions from head to toe throughout her career. Her autobiography Shocking Life sealed her own sense of connection to the color, the connotation of the hue expressing her provocative, enthralling work.

Suit, 1938-39 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum; Gift of Arturo and Paul Peralta-Ramos); Dinner jacket, 1947 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Mme Elsa Schiaparelli); Shocking de Schiaparelli perfume ad by Marcel Vertes, 1950—the perfume was first created in 1936); Boots designed by Elsa Schiaparelli in collaboration with André Perugia, 1939-1940 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Mme Elsa Schiaparelli)

The cover of Schiaparelli’s 1954 memoir.

“Ninety percent are afraid of being conspicuous, and of what people will say. So they buy a gray suit. They should dare to be different.” —One of the “12 Commandments for Women” from Shocking Life.

Written by Maggie Wilds/ denisebrain