The horror of the tragedy casts a shadow even to this day

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

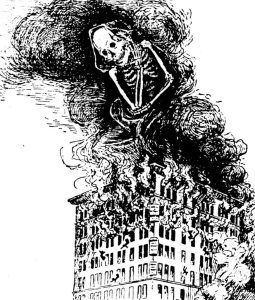

The specter of Death rises with the smoke and flames of the burning building as people jump and fall to their deaths, editorial cartoon from 1911.

On Saturday, March 25, 1911, near quitting time, a fire broke out on the 8th floor of New York City’s Triangle Waist Company and quickly spread to the 9th and 10th floors. Within minutes, 146 of the 500 employees had died in the blaze. The seamstresses—mostly young women who had recently immigrated to the U.S.—were trapped, locked inside by the management. Numerous safety violations made their rescue impossible. The women who didn’t burn alive jumped to their deaths, to the horror of the crowd on the street.

Louis Waldman, a New York Socialite, was sitting reading in the nearby Astor library.

I was deeply engrossed in my book when I became aware of fire engines racing past the building. I ran out to see what was happening … When we arrived at the scene, the police had thrown up a cordon around the area. Horrified and helpless, the crowds—I among them—looked up at the burning building, saw girl after girl appear at the reddened windows, pause for a terrified moment, and then leap to the pavement below, to land as mangled, bloody pulp. Occasionally a girl who had hesitated too long was licked by pursuing flames and, screaming with clothing and hair ablaze, plunged like a living torch to the street.

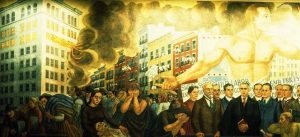

Detail, History of the Needlecraft Industry (1938), by Ernest Fiene, High School of Fashion and Industry. The mural was commissioned by the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU).

The workers were subjected to dangerous and inhumane factory conditions but it wasn’t for lack of fighting for better. In 1909, 20,000 garment workers in New York City walked off the job, and the strike lasted 14 months. They made some progress with smaller manufacturers but a big factory like the Triangle Company could afford to hold out longer than the workers.

Striking garment workers in 1909. Of those who died in the Triangle fire, dozens were teenagers as young as 14—there was even an 11-year old.

{Must see: Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives at Cornell University’s Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire Website}

On April 5, 1911, just over a week after the fire, union organizers and workers held a funeral march down New York City’s Fifth Avenue. Reports vary, but it’s estimated between 80,000-120,000 people marched for over six hours, with 300,000-400,000 people observing.

Following the tragedy, public sentiment strongly favored increased safety standards and humane working conditions, and workers flocked to strengthening unions, most prominently the ILGWU. Progress was made, much due to that terrible March day.

Workers protest after the fire, April 5, 1911.

Written by Maggie Wilds/denisebrain

Select references:

Juravich, Nick .“Look for the Union Label: A History of the ILGWU’s Iconic Jingle.” New York Historical Society, April 24, 2019, https://www.nyhistory.org/blogs/look-for-the-union-label

“The Tragic Story of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1911.” 5 Minute History, https://fiveminutehistory.com/the-tragic-story-of-the-triangle-shirtwaist-factory-fire-of-1911/

“International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union.” https://labormovement.blogs.brynmawr.edu/1915/03/26/international-ladies-garment-workers-union/

“Clara Lemlich and the Uprising of the 20,000.” American Experience, PBS.org https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/biography-clara-lemlich/

Hickey, Andrea. “The Tragedy Of The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Was A Landmark For Workers’ Rights.” Buzzfeed, Jun 2, 2018, https://www.buzzfeed.com/agh/triangle-shirtwaist-factory-fire-workers-rights-history