British Boutique movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

My name is Liz, a.k.a Emmapeelpants, and I will try to introduce you all to the vibrant design movement as much as I can. Obviously it is an enormous subject, so I have chosen some select designers and boutiques to concentrate on.

The emergence of youthful and ambitious British designers in the 1960s was a revolution in the fashion world. Quite apart from the front-runners enabling lots of other young designers to feel that they too could start their own boutique, it forced the other fashion capitals to change their outlook and methods. So radical was the new look of the era, Britain became the focus of the world, and thus its leader. For once, New York, Paris and Milan were looking to quirky old England for inspiration. British designers headed out on PR tours of America, pushing the Swinging London lifestyle and expanding their empires. It would end, in the great scheme of things, almost as suddenly as it began. Failing economy in Britain in the 1970s increased overheads and reduced sales for these designers, and as the other fashion capitals of the world fell out of love with the London look, most British designers floundered. I will try to give you a flavour of the designers involved and, within their stories, the eventual decline.

British Boutique Movement: burning brief and bright.

To start, I have put the designers and labels I know of into a tier system, which make it easier to digest and remember all the major and minor players in the vibrant British fashion scene in the 1960s and 1970s.

Top Tier

The Haute Couturiers with the British flavour. They are associated with the era more through the timing of their emergence, their popularity during that time and their collectability now.

Bill Gibb, Thea Porter, Zandra Rhodes, Jean Muir

Second Tier

The REAL stars of the period: the movers, shakers and talented kids who exploded onto the scene with a very British couture. A lot of them were the product of a strong art school scene in the late 1950s/early 1960s; Quant, Foale and Tuffin, Wainwright, Ossie and Gerald McCann are amongst this group.

John Bates, Ossie Clark, Janice Wainwright, Foale and Tuffin, Mary Quant, Gerald McCann, Gina Fratini, Alice Pollock, Jeff Banks, Christopher McDonnell

Third Tier

The true boutiques of the movement. A new kind of department store, stocked with cheap, throwaway trendy gear and with a strong concept. The true predecessors of modern, young High Street stores like Topshop and Miss Selfridge: who both sprung up in the mid-late 70s, coinciding with the demise of Biba and Bus Stop.

Biba, Bus Stop, Clobber, Annacat, John Stephen (in all his incarnations; Lord John, Lady Jane etc), Granny Takes a Trip, The Apple Boutique, Quorum, Top Gear, The Fulham Road Clothes Shop, Pussy Galore, Miss Mouse, I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet.

Fourth Tier

The celebrity boutique. This phenomenon was started by TV presenter and ‘Queen of the Mods’ Cathy McGowan in the mid 1960s, continued with Twiggy and chanteuse (and Jeff Banks’ wife) Sandie Shaw in the late 60s. Cashing in on the popularity of said starlet, these were unlikely to have been designed by them, despite what publicity material of the time might say, being more a clever marketing ploy by manufacturers. Honourable mention also goes to Lulu.

Fifth Tier

Nationwide; boutiques sprang up across the country like Pollyanna, The Birdcage and AnnaBelinda of Oxford. Inspired by their London counterparts, they would sell their own designs and select pieces by the big name London designers.

Sixth Tier

What I would describe as the commercialisation of the movement. Designers and ‘boutiques’ one knows little about these days, often a cloak for established clothing manufacturers wanting to project the boutique image. I would tentatively place Samuel Sherman in this tier because, despite the youthful image of his Dollyrockers brand, the sheer number of seemingly separate labels with his name attached might suggest he was simply a canny businessman. John Stephen (see above tier) had a similar ‘finger-in-all-the-pies’ syndrome, but he really was the KING of Carnaby Street and his influence on fashion and the business of High Street fashion is undeniable. Also the prevalent ‘QUAD’, ‘Mr Darren’, ‘Origin’ and ‘Polly Peck by Sybil Zelker’ would seem to be at the bottom of the pile in terms of price, quality and the lack of designer profile (or even existence in some cases) demonstrated in higher tiers. It has to be said though, that they did produce some mighty fine clothes which still make great alternatives to the ‘big’ names, just as they did back then!!

Quad, Mr Darren, Dollyrockers, Polly Peck/Miss Polly, Origin

Sisters Are Doing It For Themselves: The Emergence of the Young Businesswomen

The 1960s were a time of change for women in all spheres of work. The British Boutique Movement was spearheaded by a collection of young, talented and ambitious young women, eager to cater to their contemporaries in a way that fashion had failed to do for them.

The most famous of these young women is Mary Quant. She was trained in Illustration at Goldsmiths’ College and worked at a milliner’s, stitching hats for wealthy ladies. It was this awareness of the discrepencies between fashions for the privileged and for ordinary young working women which inspired her. The origins of the revolution in the 1960s lay in the Teddy Boys and Beatniks of the 1950s, who were disillusioned by post-war Britain and thus subversive in their clothes and lifestyles. Mary Quant opened her first boutique ‘Bazaar’ on the King’s Road with her boyfriend Alexander Plunkett-Green and Archie McNair in 1955, clearly a part of this new way of thinking. She initially bought clothes in to sell, but was typically frustrated with what was available to her. So she set about creating her own, in a somewhat haphazard manner which never seemed to meet the level of demand from customers.

Creating unique clothes was simply not enough for her, she went several steps further to create a unique boutique through which to sell them. They would use completely outrageous novelties to keep the shop a controversial talking point in the heart of Chelsea, one of London’s most expensive and fashionable areas. The shop window was re-styled practically every week, exhibiting new designs and taking window design to new levels with extraordinary themes and accessories.

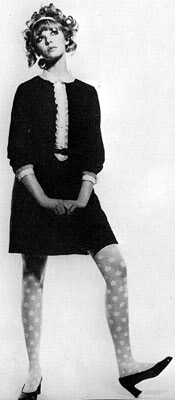

Her earliest designs don’t seem all that radical when viewed through modern eyes, they have a more beatnik quality. Skirts were shorter than they had been, but the mini was a few years off being her trademark. The notable difference in her clothes though was the naivety; simple fabrics, simple straight cut shapes or sportswear influences.

The cranberry and black striped dress from my own collection is one of the earliest pieces I have seen and is exhibited in the window display above. It is very early and despite the full skirt and frilled neckline, actually demonstrates the new simplicity she was bringing. It didn’t require a petticoat, the fabric is a very heavy, dark, naïvely striped cotton and the frills are almost childish rather than sophisticated. The dress on the right shows much of her inspiration came from the clean lines and boyish cuts of the 1920s, and would eventually influence her work in a more subtle way. She cottoned onto the zeitgeist; youth. Women were young, women wanted to look younger, women now had the spending power to buy such clothes. They didn’t want the fussy, pastel concoctions of their mother’s wardrobe, so the dramatic move towards simplicity and ‘kooky’ colours began…

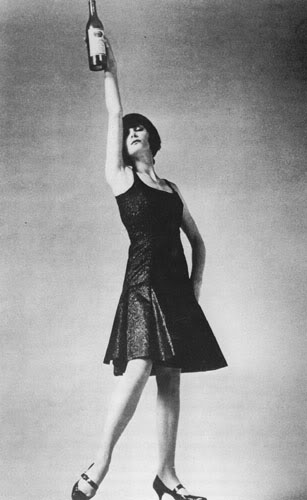

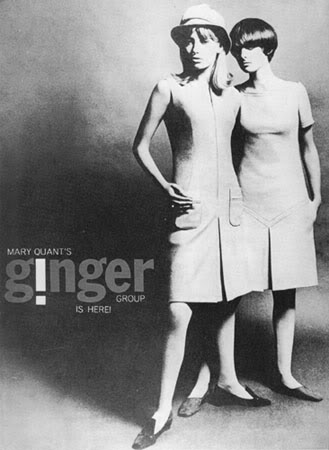

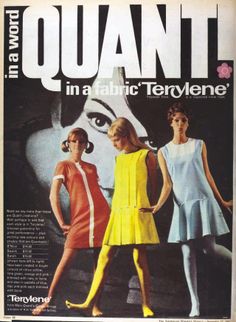

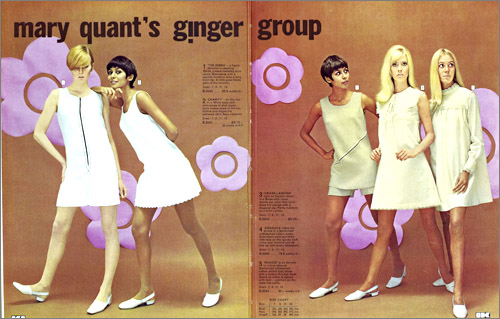

In 1963 she started the ‘Ginger Group’ label, which was the affordable branch of her empire. Although her main clothing lines was essentially ‘affordable’ to working women, she knew she could capture the younger market with a cheaper, more youth-orientated label. The Ginger Group was launched with much fanfare and celebrity endorsement:

The highlight of her design career and her most prolific period, was the period from around 1963-1967. She went to America several times, launching The Ginger Group there and designing for collaborations with several manufacturers including Youthquake (c.1965) and JC Penneys (from 1963). She had a natural ability to promote herself, combined with the sharp business mind of her now husband, Alexander Plunkett-Green. It was during this period we get the definitive ‘Quant look’, with her use of op-art, mini skirts and PVC. It’s safe to say that nearly every designer around was designing along the same lines, but the cult of Mary Quant was dominant, her range of make-up, shoes, tights and underwear helping to keep her in the customer’s eye all the time. She was even awarded an OBE in 1966, collecting the gong in a mini dress!

There is also the question of the continually disputed title of ‘Inventor of the Mini’, which is frequently attributed to Quant. Whether it be Quant, Courreges or John Bates who actually got it out first, the truth is that all three designers were not ‘inventing’ anything – merely realising the potential of the street fashion for raising hemlines. However, Quant was absolutely the Queen of the mini-skirt, using her inimitable capacity for self-publicity to style herself as the spearhead for this revolution. It was a natural progression from her early designs, moving from the youthful into the practically baby-ish minis of 1966-1967.

“There was a time when every girl under twenty yearned to look like an experienced, sophisticated thirty…All this is in reverse with a vengeance now. Suddenly every girl with a hope of getting away with it is aiming not only to look under voting age but under the age of consent.’‘ Quant on Quant, 1966.

As you can see above, the look had softened by this time – with the emphasis on femininity with frills and floral prints. The late 60s spelled the end of Quant-mania. British fashion was evolving from the signature Quant look into a softer, more romantic look with the emergence of Ossie Clark and boutique ‘Biba’. It is perhaps appropriate that the woman who defined the 1960s, was unable to adapt enough to move as successfully into the 1970s. The Ginger Group was still active, and the pieces from this time are very cute and frilly – but she was no longer a fashion leader, clearly influenced by Biba and Jean Muir (see below). Quant was now that bit older, married and less appealing to the next generation of young shoppers.

She also mimicked French designers like Cardin by licensing her name out to all areas of design (homewares, the continuing reliance on make-up, umbrellas, ponchos, beachwear etc). Her ability to license herself benefitted her financially, no doubt, and for a while the US market was still mad on Quant. However, it inevitably meant that she was no longer considered relevant as a designer because she hadn’t concentrated on evolving her style. She’s been designing ever since this time, but it is our fascination with the image the name ‘Quant’ evokes and her own over-reliance on this which has kept her firmly in the past as far as fashion goes.

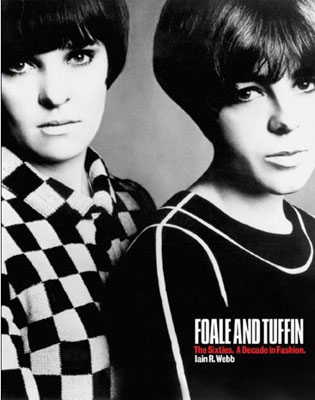

Foale and Tuffin

Quant wasn’t the only talented and strong female personality breaking through in the early 1960s.

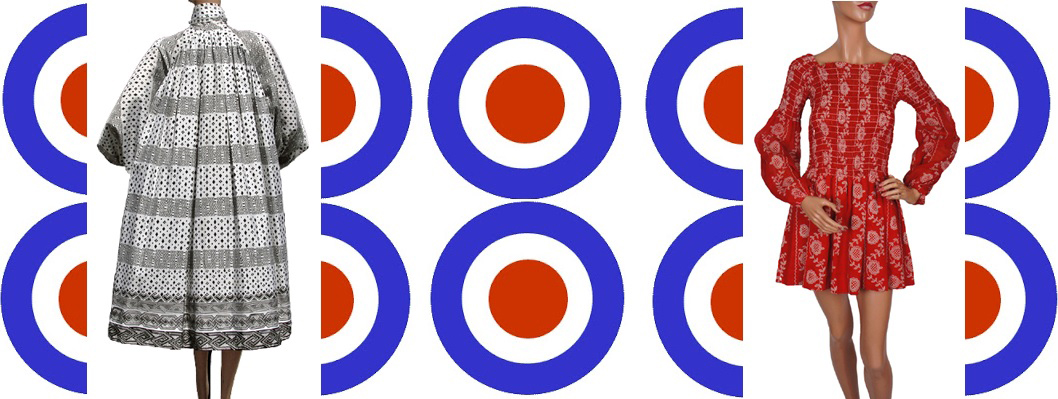

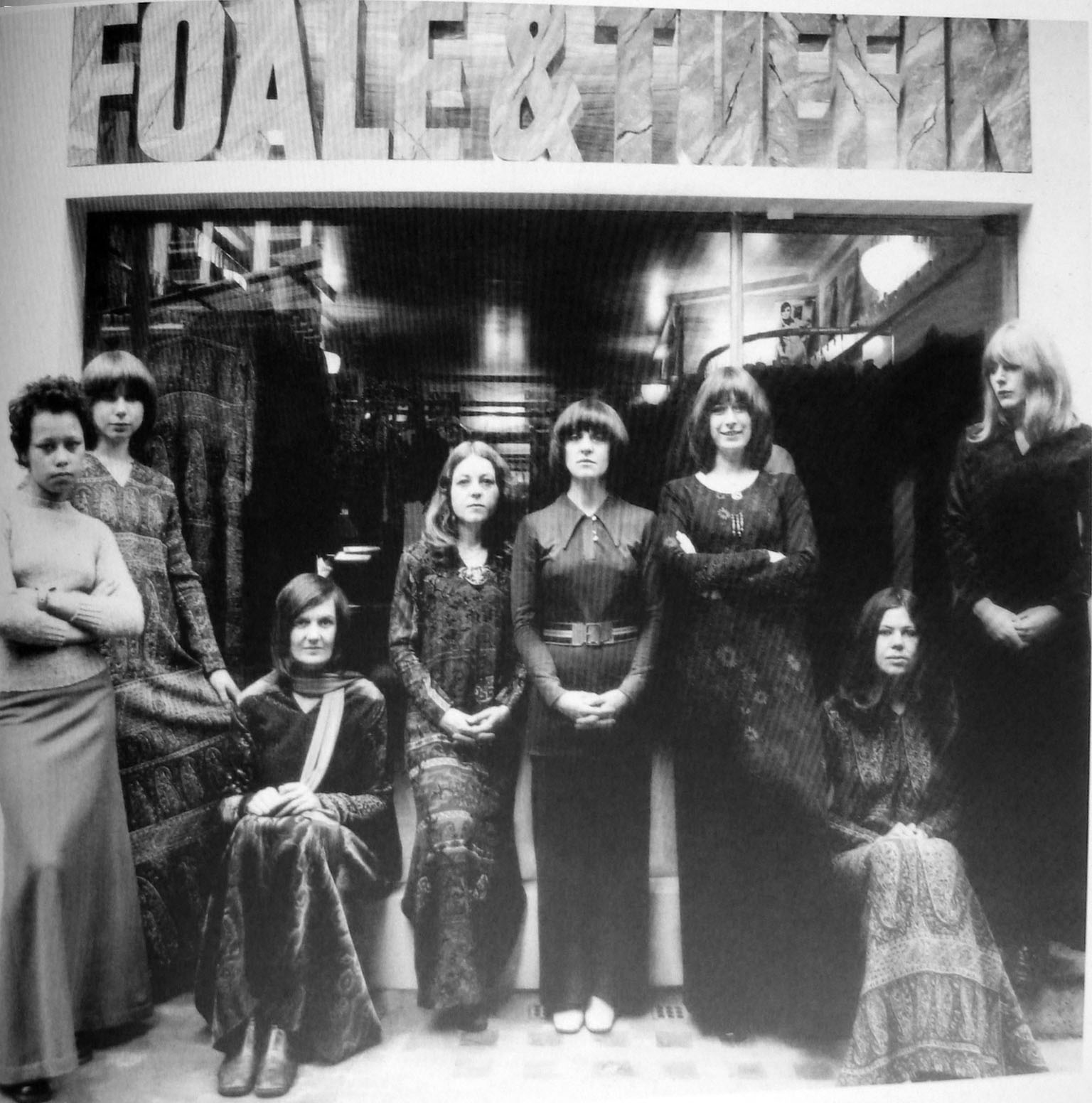

Foale and Tuffin were the true spearheads of the new female design revolution, completely self-reliant in their business where Mary Quant, Barbara Hulanick and Lee Bender were all supported by husbands and male business partners. Marion Foale and Sally Tuffin were graduates from the Royal College of Art in 1961. In 1960, Mary Quant’s partner Alexander Plunkett-Greene gave an inspirational talk at the RCA about the set-up of ‘Bazaar’. The set pattern for graduating students was to get a job at a manufacturing firm, but Tuffin and Foale rejected this route to set up in business on their own, thus changing the outlook of later students (who included Ossie Clark).

Marion Foale had been taught pattern-cutting and dressmaking at home, and refined these skills at the RCA – ensuring that she knew exactly how to create the designs she made. When they graduated in 1961, they rented studio space on Carnaby Street (before the revolution which made it a centre for London fashion). Two young women setting up on their own caused raised eyebrows from all quarters and Foale recalls “the hilarious response from wholesalers at two ‘kooky’ girls trying to source fabric and suppliers. We initially bought fabrics from Dickins and Jones and then realized that ‘wholesale’ existed.”

Completely self-sufficient, they made their own patterns and cut their first samples themselves, before opening up a shop in Marlborough Court (off Carnaby Street) in 1962. They shunned Paris fashion, concentrating on creating wearable and fun clothes for young women like themselves.

“ We suddenly didn’t want to be chic; we just wanted to be ridiculous.”

Around the same time, they discovered a love of lace – which inspired a collection of little lace dresses which were bought by the Woolands 21 shop (which, at this time, was a showcase boutique for many of the up-and-coming new London designers).

By 1963, Foale and Tuffin were firmly established in their own business and had fulfilled their ambition of achieving this without the help of a man. They were a mainstay of mid-60s Vogue, their tailoring proving extremely popular and bold use of fabric and colour catering to the kooky young girls of London.

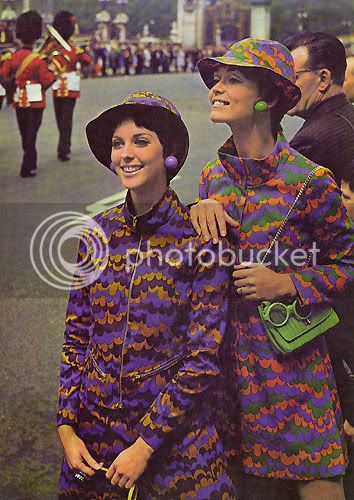

In 1963, the US firm JC Penney had brought Mary Quant on board for a series of collections – masterminded by European buyer Paul Young. Fascinated by the kooky styles emerging in London, he felt that the connection would bring new buyers to the stores – translating the new ‘accessible’ clothes to US audiences. Young moved to the ‘Puritan Fashion Corporation’, and was briefed to position them at the forefront of the youth fashion market. He created the ‘Youthquake’ label for them, and asked several young British designers to design for them. These included Foale and Tuffin. A heavy promotional tour was organised, bringing with it the new trend for vibrant, dancing fashion shows which captivated the Americans.

However, the venture was initially unsuccessful. The manufacturers cut corners, used poor quality fabrics and the clothes were quite badly made. The department stores also didn’t know what to do with the collections, as they were divided into sections for different ages and no one was quite sure where to put these quirky, ‘teen’ clothes. Young realised that the department store system would simply not work, and created specialist shop ‘Paraphernalia’ which stocked Quant, Foale & Tuffin, Ossie Clark and Emmanuelle Khan.

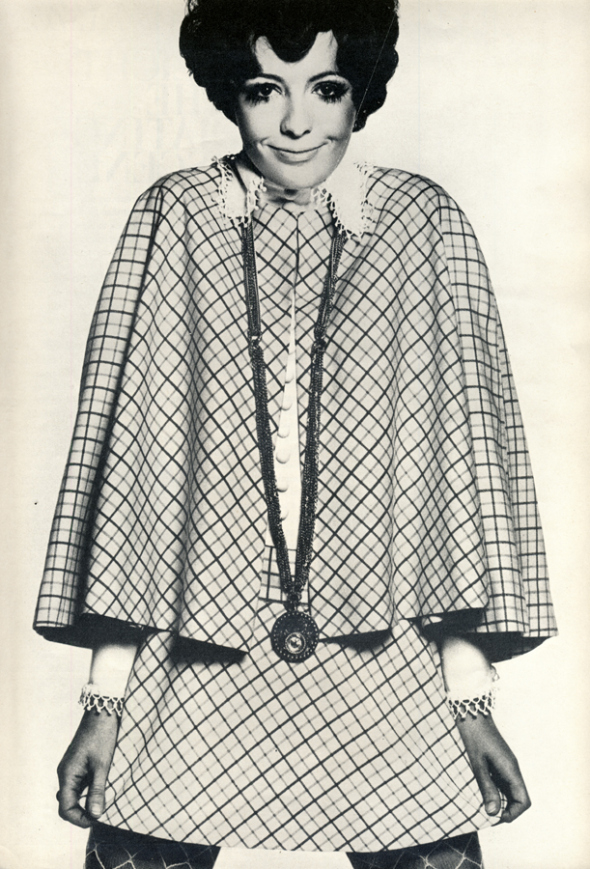

Moving into the later years of the 1960s, Foale and Tuffin continued to produce incredibly tailored outfits – this being something of a trademark for them at the time. It was still young and fun, but with a sophistication which belied their youth and outlook.

They were so highly regarded they were even chosen to create costumes for Susannah York in Kaleidoscope (1966) and Audrey Hepburn in Two For The Road (1967)

They were also becoming famous for using extraordinary fabrics, many by famed textile designer Bernard Neville, which they regularly used in some quite insane, some simply romantic and always fun outfits!

In the early 1970s, both women had got married and started families which meant their interest in fashion diminished somewhat. In 1972 they decided, very amicably, to dissolve the partnership and move on to new things. Sally Tuffin is now a highly regarded ceramics designer at Moorcroft and Marion Foale continues to design knitwear. Despite their prolific output throughout the 1960s, their clothes are as rare as hen’s teeth and they remain one of the glaring omissions in my collection. Foale and Tuffin truly represented the new position women held in fashion through the boutique movement. They managed to succeed on their own terms, without the assistance of any men and inspired countless other young women to do the same.

It’s a woman’s world: Men designing women

In an era of feminism, and where female designers radically altered the face of fashion, what about the men? A new type of male designer appeared in the 1960s, less domineering and starchy than their predecessors (like Hartnell, Amies, Steibel, Cavanagh and Morton). They were designing FOR women, catering to tastes newly set by the likes of Quant and Foale and Tuffin. That is not to say that they were mimicking their female counterparts, merely sharing their market. Young buyers were respected for their new disposable income; no longer supported by husbands and lovers, they had jobs and an unquenchable desire to look young and radical. Fashion had known nothing like it, and the male designers took this to extremes.

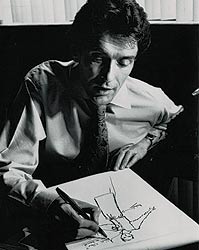

John Bates

Well I had to do it. Possibly one of my favourite designers of the period, John Bates was radical and uncompromising with his designs. He embraced the new youth movement with a similarly opinionated approach to design that the ‘old-school’ designers had in the earlier part of the century.

“I hate girls not making an effort, and with a slovenly attitude to their appearances. I often see super girls who are very nearly smashing, but not quite there, simply through lack of effort.” Adding hastily, “Of course this applies just as much to men!” Designs on Men. 19 Magazine. April 1969

However, unlike them, he was fascinated with this dominance of youth, confidence and the entirely new fashionable figure. Since his career continued until the end of the 1970s, I have decided to concentrate on his earlier work which is most representative of his contribution to the Boutique movement.

The true background to his association with the ‘Jean Varon’ name is fuzzy, depending on where you read about it. Bates himself claims he was invited to start the label and that he came up with the name himself, whereas other sources claim he was invited to be sole designer for the existing Jean Varon firm. He had no formal training in fashion, having worked in journalism and, allegedly, as a window dresser for Mary Quant’s Bazaar boutique. He trained at Herbert Sidon of London in the late 50s and started at Varon in the early 60s, possibly 1960 (again, depending on the source you read). After early attempts at radical design were thwarted by what large department stores (such as Fenwicks) required for their rather old-fashioned clientele, Bates eventually hit his stride as a designer in around 1964, catching the attention of British Vogue (who were always eager to find the ‘next big thing’). The increasing popularity of Mary Quant, Foale and Tuffin et al enabled Bates to break the somewhat ‘staid’ mould he had been forced into.

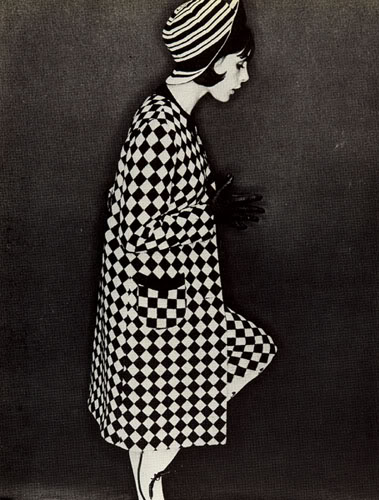

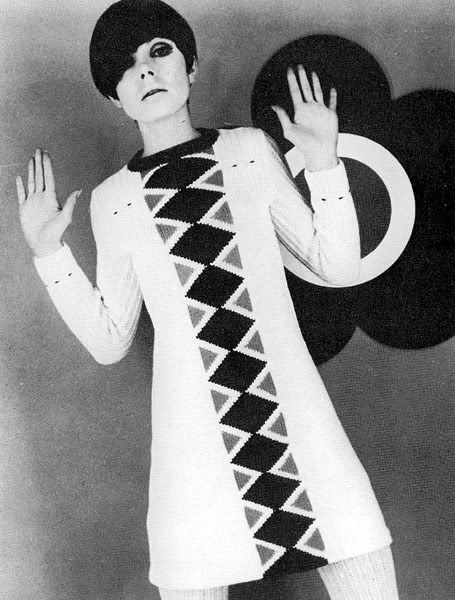

He took the gradually rising hemlines and raised them higher. He took the new, more boyish lines and made them straighter. He took bizarre and often unworkable textiles, experimenting with how he could use them. He was also amongst the first designers to use the emerging op-art textiles in his work. Jean Shrimpton appears to have been the natural model for his work at this time.

When there was no more leg to be revealed, he started removing fabric from the midriff – creating the cut-out effect, filled with transparent or loose-weave fabrics.

He was the first designer to really see the external potential of underwear; there really is a very fine line between your average 60s undies and some Bates outfits!

Also radical in his choice of fabric, Bates was amongst the first to experiment with PVC and in this piece in my collection, a type of bacofoil!! The body of the dress is made from a textured synthetic which has such a stiff feel that, teamed with the foil trimmings, renders the dress almost entirely unwearable. I’m sure it WAS meant to be worn, but these early pieces were very heavily stylised.

His designs for Emma Peel in Season 4 of The Avengers, demonstrated a youthful arrogance and determination. It had been a commonly held belief that Television could not cope with bold patterns and shapes, but Bates designed a large number of costumes with lines, circles and stripes in a demonstration of his skill as a designer. They worked and were such a departure from the clothes commonly seen on Television that they were an instant hit, sold out in shops across the country and secured his fame and popularity as a designer. He also defiantly raised her hemlines, left no hem so they could not be lowered again and showed her midriff. All of this was designed before the mini had really ‘hit’ the country, and was broadcast at the same time it did hit. He also created controversy by eliminating the ‘leather’ element of the Cathy Gale and earliest Emma Peel episodes. He used PVC with stretch jersey, snakeskin and fur instead for a softer, more feminine look.

Bates was also famed for his radical approach to accessorizing, which was demonstrated in his commissioning the beret (by Kangol), gloves (by Dents), tights and shoes (by Edward Rayne) which were integral to the Emma Peel wardrobe. He wanted control over the entire look, designing hats and tights to be manufactured by others for the sole purpose of matching his clothing designs.

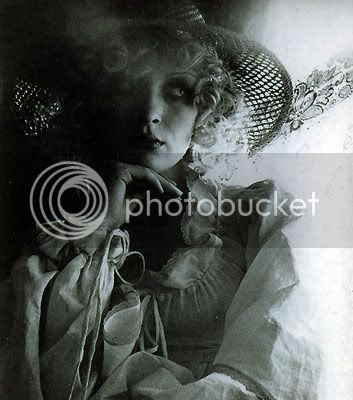

Aside from these radical and totally innovative pieces which became his trademark, Bates was also famed for his feminine designs – something some lesser male designer might have forgotten in the pursuit of total innovation and attention seeking. His designs were unashamedly attention seeking, but retained the femininity which kept his customers coming back for more. His signature designs included lacey babydoll mini dresses and empire line maxis in a wide range of colours and patterns.

Bates had a design career longer than many of his contemporaries. Financially backed as designer for Jean Varon, he had a certain degree of freedom to adapt to market forces. The 1970s saw the fall of many designers who couldn’t keep up with the changing needs of their now older customers. Things were coming full circle back to a more conservative mainstream fashion, and the street look was back under the control of people on the streets. Punk arrived in the mid 70s, leaving many designers out in the cold by both the establishment and the young people. Bates somehow navigated his way through this with designs aimed at an older, more conservative audience

However, it was his determination to have his own-name label which eventually edged him out of the industry. ‘John Bates’ clothes were more ‘couture’, more expensive and more in the vein of his contemporaries like Bill Gibb, Zandra Rhodes et al whose expensive and elegant designs were what the Vogue editors now looked for.

The label wasn’t an enormous financial success though and (according to some biographies I’ve read) bankrupted him, ‘Jean Varon’ was no longer fashionable and Bates decided to leave the industry before he could get sucked into the rag trade – anonymously designing for manufacturers.

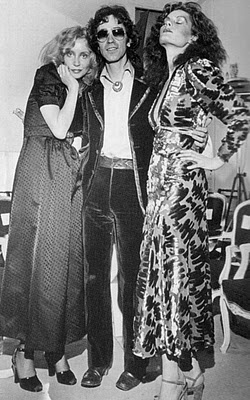

Less content to adapt to market forces was designer Ossie Clark. Used to getting his own way, and with absolutely no head for business, he was hit hardest by the changing face of fashion in the mid 70s. For ten years, he was the darling of British Fashion – feted worldwide and allowed a fairly free hand over his designing. The late 70s brought with it a long period in the fashion wilderness for Ossie, his curvaceous, form-fitting and romantic designs didn’t adapt well to the conservative direction Vogue was taking – nor to the recycled, torn and harsh Punk-look.

Ossie Clark

Ossie is not a designer you would associate with the word ‘radical’, but there was something quite deliciously so about his emergence as a designer in the 1960s. Training at The Royal Academy and something of a prodigy in his time there, Ossie’s first pieces to feature in Vogue in 1965 were undeniably youthful, brilliantly well cut and more form fitting than his contemporaries. His talent was spotted immediately, and he was taken on by designer Alice Pollock to design for her newly established boutique ‘Quorum’. However, there is almost something derivative about his use of op-art prints, simple shapes and mini dresses. These were being produced by most designers by this point and you certainly don’t feel that Ossie had quite hit his creative stride yet.

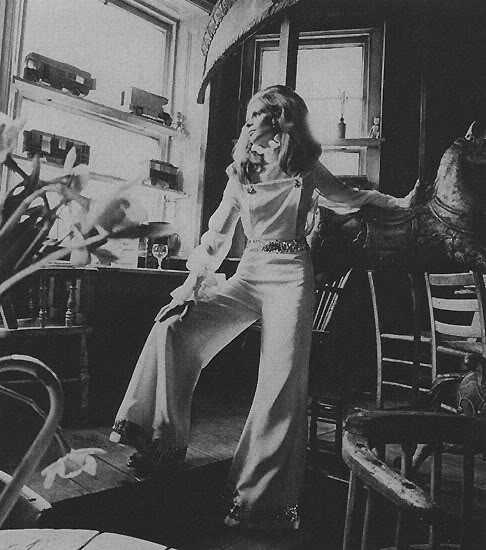

Whether it was the Ossie influence, or simply the influence of the changing youth scene in the late 1960s it is hard to know, but his late 1960s designs began to really change perceptions about clothes for women. Ossie adored the female form; breasts, waists, bottoms and all. The radically ‘straight’ look of the mid 1960s dollybird wasn’t appealing to Ossie in the same way it was for other designers.

‘I found the mini skirt restrictive. With the bias cut you could end up with the most extraordinary patterns.’ Ossie Clark

Whereas Bates’ response to the dead end street of the mini skirt was to cut out from elsewhere to the point where there was barely any fabric left, Ossie’s response was to lower the hemline again so that he could manipulate it from that point. Inspired by the fluid, body conscious designs of Vionnet in the 1930s, he experimented with more fluid fabrics like satin, chiffon and his trademark moss crepe. These early designs are a real signpost to where he was headed.

Ruffles, ties and buttons appeared (he couldn’t stand zips and did anything he could to avoid using them) and the whole look softened. His muse was his wife Celia; petite, curvy and ultra-feminine. She was also providing textiles for him, which in turn inspired new designs to accommodate them. So important was Celia to Ossie, that he cited her textiles as the main reason behind his success and jealously refused to let anyone else use her designs. The only designer who ever DID, was their friend Janice Wainwright who used a few Celia textiles in the late 60s for Simon Massey, before Ossie then demanded complete exclusivity.

More so than any other designer, he designed for what women wanted. The appeal of the androgynous mid 60s silhouette was wearing off and the slinky, sexy and un ashamedly glamourous Ossie silhouette began to dominate. He, Celia and one of his favourite designs were immortalised in popular culture through Hockney’s portrait of them (itself inspired by Jan van Eyck: The Arnolfini Portrait and Mr. and Mrs. Andrews by Gainsborough)

In his enforced creative partnership with the company Radley from 1969 (Quorum was in pretty bad shape financially, despite its critical success and Al Radley bought the company), he also increased his output and dominance of the market. The earliest designs differ little from the ‘couture’ pieces, save for the insertion of zips and some slight modifications by Radley designer Rosie Bradford. Over a relatively brief period of time, the quality of the Ossie for Radley output diminished. They seemed to frequently rely on ‘old favourites’, and the pulling power of a dress having a Celia print. Below right is one of the staples of the Radley output, a typical Ossie cut with the requisite buttoned front, enormous sleeves and rounded collar

Far from being a one-trick pony though, in his own label work he continued to carve his reputation as a master tailor.

As I have mentioned before, several designers were hit quite hard by the failing economy and the advent of punk in the mid-late 1970s. Ossie had always been stubborn, and a poor businessman. Without Alice Pollock to prop him up, he was unable to cope in the changing industry. He and Celia were divorced in the mid 70s too, which left him without one of his main inspirations. The relationship with Radley/Quorum ended in the late 70s, and designs from this period show a certain lack of clear direction.

He spent the later part of his career teaching young designers like Bella Freud. Tragically, he was murdered by his boyfriend in 1996, and never really got to see the resurgence in popularity of his designs.

The Boutiques – The Namesakes of the Movement

Annacat

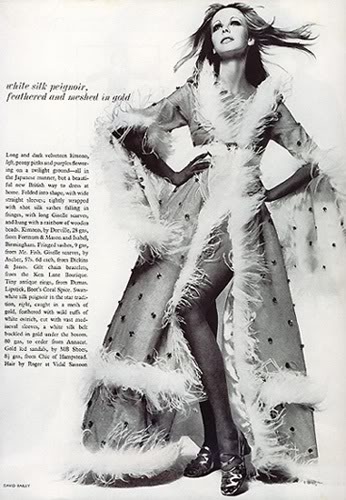

Formed in 1965 by friends Jane Lyle and Maggie Keswick, Annacat was the Biba of The Brompton Road. Although little is known about the origins of the boutique, it is easy to show the sense of fun and youthful enthusiasm which encapsulates the Boutique Movement through the designs of Annacat. They were highly favoured by British Vogue (something which Biba and Mary Quant struggled with throughout the 1960s, despite their fame and obvious charms), and the two female designers would appear to have been very ‘in’ with the London scene at the time – which might explain their favoured status. There is a real sense of fun and decadence about their pieces, regularly trimmed in ostrich feathers, printed in feminine, swirling psychedelics and with historically influenced, sexy shapes. I have often regarded Annacat as the truly girly version of Foale and Tuffin. Party girls, party clothes and (judging by some comments I’ve read online by those who went there) a real party atmosphere in the boutique itself.

Annacat founder Janet Lyle with Patrick Lichfield in Vogue, September 1968. Janet Lyle wears her own sea green velvet dress, Patrick Lichfield his own yellow shantung shirt. Both destined for New York where Annacat has opened a boutique at 924 Madison Avenue. Janet Lyle’s dress is full length, with small bodice, cascading white lace sleeves sewn with green satin ribbons. Patrick Lichfield’s shirt, with ruffles and a detatchable sash to tie in a large floppy bow, is from his first collection of men’s shirts which will be sold in a special boutique inside the New York Annacat. Happily, they are both available at the London Annacat, too, £33, and 15 gns to order, from 270 Brompton Road, SW3.

Annacat clothes were decadent, wild and a tad impractical – in my time, I don’t think I have ever seen any Annacat daywear!! One of their signature looks was feather trims, as shown in this photo from Vogue,

They even managed to give some glitz to dungarees!

When the girls weren’t adding sequins and feathers to things, their own take on the pseudo-historical trend was unashamedly, girlishly romantic. As you can see on the top picture of Janet Lyle, they were fond of velvets, period bodice styles and Liberty prints.

The shop also stocked concessions by other designers (such as Patrick Lichfield, above), amongst the Lyle and Keswick pieces. Apparently, the boutique was the first London outlet for Laura Ashley in the late 1960s – before her own shop opened on the Fulham Road.

Annacat was sold wholesale in 1970, presumably there weren’t enough customers clamouring for sequin trimmed dungarees(!), and failed to continue with the critical success of the early years with a different designer at the helm. From being a seemingly permanent fixture in Vogue throughout the late 1960s, I haven’t seen anything of them in my 1970s editions. Perhaps proving that the main reason they were so successful in the first place had been the personality of the two young party girls who started it!

The boutique aspect of the movement had started to dwindle at this point. Despite the optimism behind the expansion of Biba into the Derry and Toms building in High Street Kensington, most boutiques were struggling to cover overheads – perhaps the sheer number of inexperienced youngsters running their own businesses was always doomed to fail as Britain moved into the 1970s: a time of unemployment, strikes and precariously unstable economy. The aforementioned ‘Biba’ was perhaps the poster child of the boom and

bust of the Boutique phenomenon.

BIBA

Biba truly revolutionised the Boutique as a concept. Opening in 1964 on Abingdon Road, Kensington by Barbara Hulanicki and her husband Steven Fitz-Simon, Biba was aimed at young women, with moderate disposable income who would have felt somewhat disenchanted with the prices at Bazaar, Foale & Tuffin et al. Despite the fact those shops and designers had started with the best of intentions to design for their contemporaries and make it affordable, sadly the prices were still slightly out of range for the average teenager and young women with modest salaries. The clothes were never intended to be in fashion for very long, and the girls naturally wanted new outfits to wear each Saturday night. The first shop was an old chemists, and Barbara thrived on the dark and mysterious interior of this slightly dilapidated old building – seizing on the potential to do something vastly different to the bright and open feel of ‘Bazaar’. It inspired the interior design of the three subsequent premises Biba would occupy.

The second Biba shop on Kensington Church Street

The clothes were cheap, they were (initially at any rate) bright and VERY young. By the time they had move to new premises at Kensington Church Street in 1966, they were attracting a wide range of clientele – from schoolgirls to pop stars. Cathy McGowan was regularly seen in Biba on TV show ‘Ready, Steady, Go’, which gave them a huge new audience of young women – all desperate to get the look. Other manufacturers were so desperate to get a piece of the action, they would buy Biba to copy. Hulanicki said: “We must have been the only designers who were copied at twice the price”.

1967 print Biba outfits

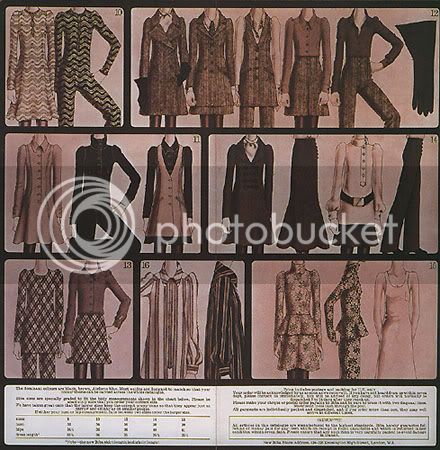

In 1968, they started a mail order branch of their company. This enabled them to offer their unique look to girls across the country – and democratized the boutique movement even more, you didn’t have to live in London to buy Biba!

Left: Biba mail order catalogue, late 1960s. Right: Black lace high neck blouse – illustrated in the catalogue – bottom right.

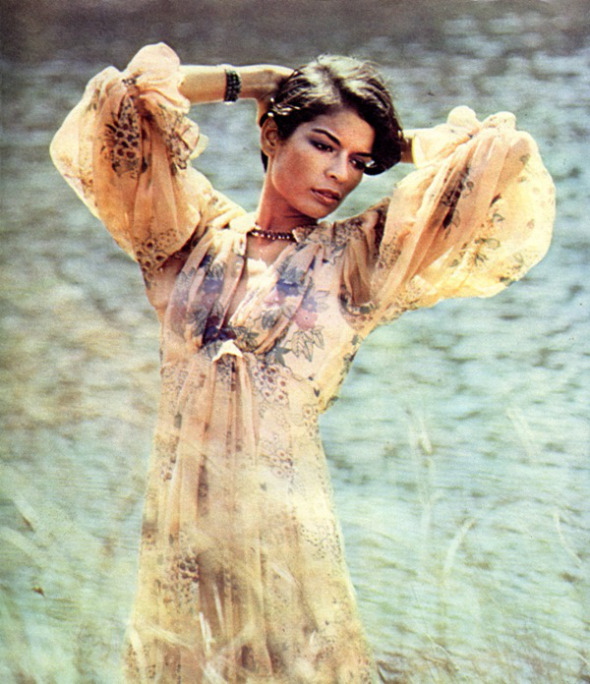

In these catalogue illustrations, we see the physical ideal that Barbara Hulanicki designed for – somewhat in her own image. High, tight armholes for skinny arms, small breasts, long gangly legs, curly hair and a doll-like application of make-up – all smudgy eyes, rosy cheeks and rouged lips. The colours also gradually became more ‘sludgy’ and retro, Hulanicki said she had disliked the colours from her childhood, when older ladies would wear them, but when she applied them to her clothes, it put a whole new perspective on it.

Left: Typical Biba colour palette. Middle: Late 1960s broderie anglaise mini dress. Right: An archetypal Biba girl

They were also famed for their prints, which quickly became more sophisticated and 20s/30s inspired than the prints shown above from 1967.

Left: Print pieces from the catalogue, late 1960s. Right: Print jersey top and skirt ensemble. The top is low cut and tight fitting and the skirt has four splits which practically reveal all!

Biba even managed to get into that other great British icon, Doctor Who. Assistant Jo Grant was conceived as something of a typical young woman of the time, and Katy Manning was definitely a typical Biba girl with her cute face, feathered blonde hair and tiny frame. The costume designer decided to regularly put her in Biba, which was later interestingly contrasted with assistant Sarah-Jane Smith who was regularly seen wearing Kensington High St. rivals ‘Bus Stop’!

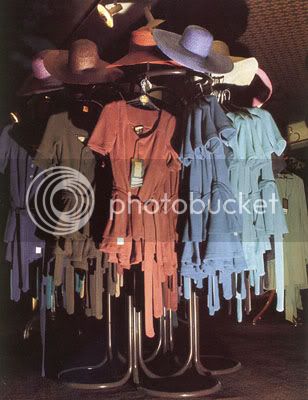

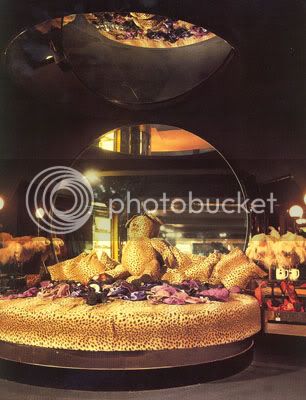

It was the late 1960s in which Biba thrived. The ‘Swinging London’ label was starting to look tired and the mood of the country was becoming far more ‘retro’, with a move towards the romance and decadence of the past. Biba perfectly encapsulated this mood, along with the country-girl chic of Welsh designer Laura Ashley, and it cemented Hulanicki’s resolve to create a complete Biba emporium inspired by the department stores of the 1920s but with a very relaxed atmosphere. She, apparently, insisted that no shop assistant should ever say ‘can I help you madam’ or make any customer feel inferior, another example of the classless shopping Utopia she was creating. This ambition was truly realised when, in 1973, she was able to take over the old Derry and Toms building on Kensington High Street (just round the corner from where Biba had been). Vast amounts of money were invested in the interiors, creating one of the most decadent and ambitious shops ever to have existed. It was dark, lush, shiny and designed to be as little like a ‘shop’ as possible. They even had a restaurant at the top, where bands like the New York Dolls would come and play!

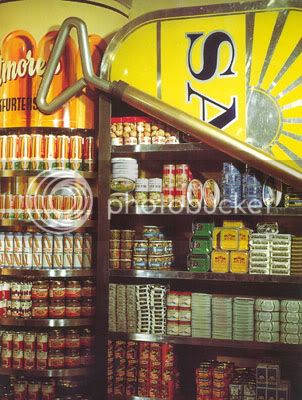

The interiors of ‘Big Biba’ in 1973

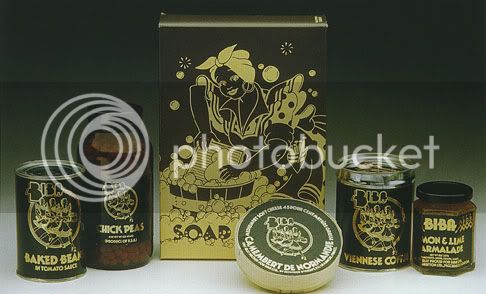

They were selling the Biba lifestyle. Food, make-up, homewares, children’s clothes, menswear….you name it, they sold it.

Soap Flakes, Cheese…..

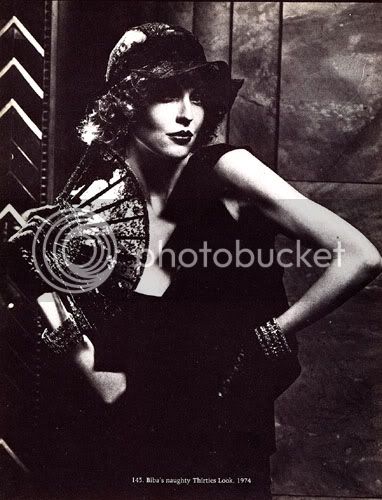

With the new store, came another approach to design. In an era of Glam Rock, where everything was sparkly and big – Big Biba came up trumps with sequined sweaters, enormous platforms and shiny fabrics.

Sequined Biba dress I recently sold on eBay.

They also ran riot with the deco inspiration:

Biba’s naughty Thirties look, 1974

Hulanicki had an uncompromising vision. Not one style she designed was made more than 500 times. She refused to have strip lighting in the store to eliminate the amount of shoplifting. She wasted piles of moss crepe if it happened to be in last season’s colours. Girls would buy each style in all the different colours available, queuing to get the latest batch. It was this throwaway mentality which makes the clothes so collectable today, they genuinely weren’t made to last. Unfortunately, cheap and cheerful did not go very well with opulent decor and waste. Biba was losing money all the time, and the economy was in a sharp downturn by 1975. Big businesses were taking over the High Street, and there was simply no room for quaint little Biba. The store was closing, people came and scavenged from piles of clothes, make-up and feathers to take their own little piece of Biba. By the end, people were just walking out without paying – Biba had always been notoriously badly hit by shoplifters and they weren’t about to stop now. 1975 was probably the watershed for many of the boutiques and designers. The demise of Biba was felt by all, it had seemed so untouchable and the embodiment of the Boutique dream.

Written by emmapeelpants 2005