Remember the 90s when everyone wore black until a darker shade came along? What is it with colour? Brown became the new black in the late 1990s but then a riot of colour exploded each spring of the new millennium that offered a playful palette for hot summer months, only to be shelved each autumn for a return to neutrals. Fashion, is… well, fashion. And it must change if for no other reason than the sake of change.

Colour may be a tool of seasonal fashion fun but in the past it could represent status better than a Hummer, and technological wizardry better than any Ipod that can carry a billion tunes.

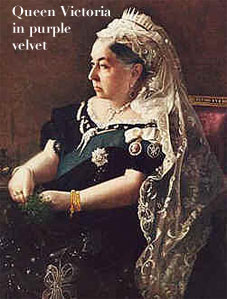

The first colour that carried fashion weight was purpura; (Latin for purple) was made from the putrefied crushed shells of Murex, a mollusk, and was more expensive than any colour ever procured in fashion history. Emperor Aurelian refused to let his wife buy a purpura-dyed silk garment in 273 CE because the cost was literally its weight in gold. Seven hundred years previous to this domestic dispute, purple robes had been accessioned into the royal treasury of Persia. Alexander the Great discovered this multi-million dollar vintage hoard nearly two hundred years after their being stowed away.

Fashion however, has always been an art of invention, interpretation, and imitation. By 300 CE a mixture of red and blue dyes made a new, more affordable purple, which was a good thing since the Murex had been harvested to near extinction. Knock-offs however, have always plagued fashion and the late 4th century Emperor Theodosium of Byzantium issued a decree forbidding the use of purple except by the Imperial family. Death was the result of breaking the edict.

Red was the next rage to affect fashion. In Europe the madder plant’s roots produced a ruby red.

As early as 1321 Brazilwood, found in the East Indies, was being used to produce a brighter red colour. In fact it was the discovery of the red dye bearing Brazilwood trees found in South America that gave the present country its name. In Central America it was cochineal, a dye derived from an insect’s body that produced a brilliant red. After the Aztecs conquered the Mayans in the 15th century eleven Mayan cities paid yearly tributes to Montezuma with, among other items, bags of cochineal dye. Around the same time, in 1464, Pope Paul II introduced ‘Cardinals’ Purple’ which was really a crimson red derived from the kermes insect, a distant cousin of the cochineal.

The conquistadors found cochineal in Mexico and, quickly realizing its potential as a cheap substitute to kermes, began exporting it to Spain in 1519. The intensity and clarity of the red was improved a hundred years later with the addition of tin in the dye bath. This red became the standard colour of foxhunter’s coats, known as hunting pinks, even though the colour was scarlet red. The British army also adopted cochineal dyed wool tunics after which they became famously known for as ‘red coats’.

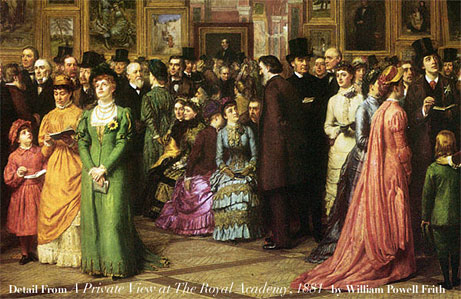

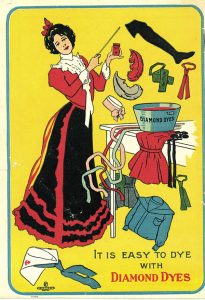

However, it was the Industrial Revolution during the 19th century that gave us the riot of colour we can now choose from, if fashion designers let us.

While looking for a cure for malaria in the 1850s, English chemist William Henry Perkin discovered aniline dyes, a byproduct created from distilling tar left from coal that was ‘cooked’ to produce gas for commercial use. The first aniline dye produced in 1856 was mauve. Although the earliest mauves faded easily in sunlight, a new colour industry was born and magenta, fuchsia, violet, as well as a plethora of blue and green colours quickly followed.

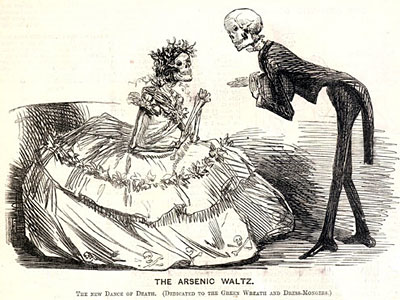

The only bright green that had been available until the 1860s was achieved through the use of arsenic. Needless to say this colour became dubbed ‘poison green’ but by the 1870s new aniline greens had replaced arsenic. In the late 19th century intense yellows and blues were known as ‘electric yellow’ and ‘electric blue’ after the brightness of the colours that emanated at an electric bulb’s intensity. Aniline dyes produced a variety of shades of every colour imaginable by the 20th century but anilines didn’t meet with everyone’s approval.

In 1900, the Shah of Persia, Mozaffer ed Din, prohibited the use of aniline dyes for carpets. Unlike Emperor Theodosium however, death was not the penalty. Instead, any rugs made with aniline dyes were seized and publicly burned, and fines equaling double the value of the merchandise were levied, potentially ruining the carpet merchant’s reputation and bank account.

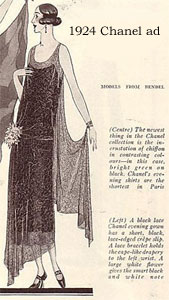

In the 20th century fashion designers took to instilling taste with every seasonal collection. The French have long had a passion for naming colours and making them fashionable one season and unfashionable the next. One season it might be vert de l’eau, shell pink, and putty, followed by navy, lime and charcoal the following season. This was one way to ensure that fashionistas continued to shop rather than rely on last season’s clothes. Some colours became associated with designers. Chanel promoted the little black dress in the 1920s; Schiaparelli single-handedly launched shocking pink in the late 1930s; black and brown were a combination mastered by Balenciaga in the 1950s, and nobody could mix every hue on the colour wheel into one pattern like Emilio Pucci did in the 1960s.

So whether it’s a riot of jewel tones or a neutral beige palette that is in style, just wait a season or two and an array of pastels or a return to black will surely follow. Besides, you can wear what you like – fashion mavens may disapprove but Theodosium won’t sentence you to death if you don’t comply.

Written by Jonathan Walford